As I sit and write this column, my typical tidal volume is somewhere around 500 mL with a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, which gives a minute ventilation of 8 liters per minute (0.5L x 16 BPM = 8 LPM), well within the range of a typical nonrebreather mask (NRB) flow, which is classically 10 to 15 LPM. However, when metabolic demands extend past typing, such as to compensate for an underlying metabolic acidosis, tidal volume and respiratory rate both increase, with peak minute ventilations well above 80 LPM seen in healthy individuals during exercise.1,2 At its usual flow rate, the NRB will not deliver anywhere near the flow of gas needed to match the patient’s underlying minute ventilation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: December 2025 (Digital)

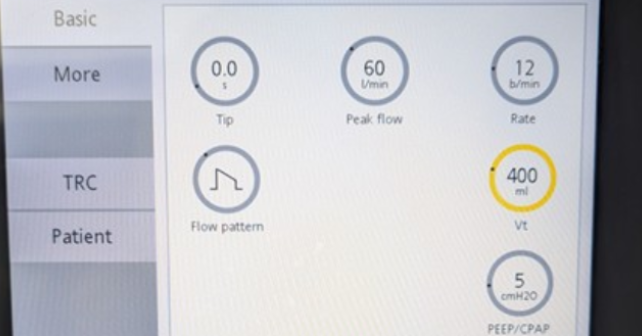

FIGURE 1. Setup screen of a mechanical ventilator. Note the shape of the flow pattern (middle left), with the highest flow rate at the beginning of the breath and then a deceleration as the breath tapers off. The peak flow on this ventilator is set to 60 liters per minute (upper row, center). Photo courtesy of Dr. Paul Jansson. (Click to enlarge.)

To add insult to injury, the respiratory phase is not linear, with most of the volume delivered in the initial moments of inspiration. This is the reason that the mechanical ventilator is typically set to have an inspiratory flow rate of at least 60 LPM which then tapers off as the breath is delivered.3 (Figure 1) Whenever the minute volume increases beyond what is supplied by the NRB, room air will be entrained from outside of the mask, lowering the Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FiO2) delivered. Therefore, for most patients with increased minute ventilation, their respiratory demand will be beyond what is provided by the NRB.

Nonrebreather masks also come with their own set of challenges. While most clinicians instinctively adjust the regulator to provide the requisite 10-15 LPM to ensure the reservoir bag inflates, flow rates below 10 LPM can cause the mask to serve — despite its name —as an inadvertent CO2 rebreathing device, and iatrogenic hypercapnia resulting in patient harm has been reported.4 Because the mask entirely covers the face, the NRB is uncomfortable, interferes with speaking and eating, and can be an aspiration risk and lead to pressure injuries, so it is a poor choice for long-term use. Due to the combination of these factors, many hospitals require ICU admission for patients on a nonrebreather, even if high flow nasal cannula therapy is allowed on the ward, which is a counterintuitive and idiosyncratic policy. Therefore, for virtually all patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, I prefer to use heated high flow cannula therapy rather than an NRB, particularly since it may allow me to spare an ICU admission.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Why the Nonrebreather Should be Abandoned”