As I sit and write this column, my typical tidal volume is somewhere around 500 mL with a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, which gives a minute ventilation of 8 liters per minute (0.5L x 16 BPM = 8 LPM), well within the range of a typical nonrebreather mask (NRB) flow, which is classically 10 to 15 LPM. However, when metabolic demands extend past typing, such as to compensate for an underlying metabolic acidosis, tidal volume and respiratory rate both increase, with peak minute ventilations well above 80 LPM seen in healthy individuals during exercise.1,2 At its usual flow rate, the NRB will not deliver anywhere near the flow of gas needed to match the patient’s underlying minute ventilation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: December 2025 (Digital)

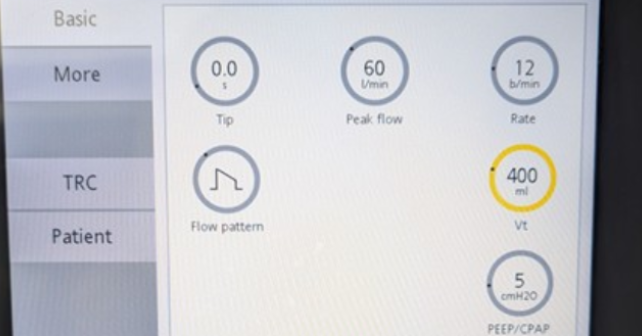

FIGURE 1. Setup screen of a mechanical ventilator. Note the shape of the flow pattern (middle left), with the highest flow rate at the beginning of the breath and then a deceleration as the breath tapers off. The peak flow on this ventilator is set to 60 liters per minute (upper row, center). Photo courtesy of Dr. Paul Jansson. (Click to enlarge.)

To add insult to injury, the respiratory phase is not linear, with most of the volume delivered in the initial moments of inspiration. This is the reason that the mechanical ventilator is typically set to have an inspiratory flow rate of at least 60 LPM which then tapers off as the breath is delivered.3 (Figure 1) Whenever the minute volume increases beyond what is supplied by the NRB, room air will be entrained from outside of the mask, lowering the Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FiO2) delivered. Therefore, for most patients with increased minute ventilation, their respiratory demand will be beyond what is provided by the NRB.

Nonrebreather masks also come with their own set of challenges. While most clinicians instinctively adjust the regulator to provide the requisite 10-15 LPM to ensure the reservoir bag inflates, flow rates below 10 LPM can cause the mask to serve — despite its name —as an inadvertent CO2 rebreathing device, and iatrogenic hypercapnia resulting in patient harm has been reported.4 Because the mask entirely covers the face, the NRB is uncomfortable, interferes with speaking and eating, and can be an aspiration risk and lead to pressure injuries, so it is a poor choice for long-term use. Due to the combination of these factors, many hospitals require ICU admission for patients on a nonrebreather, even if high flow nasal cannula therapy is allowed on the ward, which is a counterintuitive and idiosyncratic policy. Therefore, for virtually all patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, I prefer to use heated high flow cannula therapy rather than an NRB, particularly since it may allow me to spare an ICU admission.

Enter the Hero…High Flow Nasal Cannula

The high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), also known as the heated, humidified high flow nasal cannula —among other names5 — has revolutionized the treatment of hypoxemic respiratory failure the same way that noninvasive ventilation (NIV) revolutionized the treatment of hypercapnic respiratory failure. The HFNC is a dedicated device that allows for gas flow of up to 60 to 70 liters per minute, compared with up to 6 liters per minute compared to a traditional nasal cannula. With HFNC, you can also precisely adjust the oxygen concentration from 21 percent to 100 percent.

In addition, these devices also typically heat the air to body temperature and provide humidification, making the high rate of gas flow less irritating to the nasal mucosa and allowing for long-term use. When compared to NRB masks, HFNC is more comfortable, allows the patient to speak and eat, and is a lower aspiration risk.

FIGURE 2. High Flow Nasal Cannula controls. Note the temperature (34o C), the flow rate (60 liters per minute), and the FiO2 (75 percent). Photo courtesy of Dr. Paul Jansson. (Click to enlarge.)

In comparison to conventional oxygen delivery devices, HFNC allows for more precise titration of both flow (liters per minute) and oxygenation (FiO2). (Figure 2) When adjusting HFNC, typically the flow is titrated to match the patient’s work of breathing and respiratory rate, while the FiO2 is titrated to match the patient’s oxygen saturation (SpO2).

With much higher flow rates than a conventional nasal cannula or nonrebreather mask, HFNC can more closely approximate the patient’s respiratory flow dynamics. HFNC can also provide CO2 washout of anatomic dead space and provide a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), although that PEEP is drastically reduced when the patient’s mouth is open.7

Compared to conventional oxygen therapy, HFNC has been shown to reduce rates of endotracheal intubation8 in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.9 Evidence is mixed when compared to NIV for preoxygenation for intubation,10 although the combination of HFNC and NIV appears to be better than either therapy alone.11 HFNC may be left in place during laryngoscopy to provide CO2 washout and apneic oxygenation and is likely better at preventing hypoxemia than conventional oxygen therapy.12

Flush Rate Oxygen as a Makeshift HFNC

FIGURE 3. Oxygen regulator in our trauma room. Note that the markings on the side stop at 15 liters per minute, but the sticker to the right of the regulator knob indicates a maximum flush rate of 60 to 80 liters per minute. Photo courtesy of Dr. Paul Jansson. (Click to enlarge.)

HFNC requires a dedicated device and typically requires a respiratory therapist for initiation, limiting its use for emergent hypoxemia or in out-of-hospital settings.13 If you are waiting for the RT to bring the HFNC, or if you don’t have HFNC at your institution, utilizing flush rate oxygen can approximate the therapy in a pinch. Most wall-mounted regulators have clearly demarcated lines showing the precise amount of oxygen delivered between 0 and 15 liters per minute but are well capable of delivering oxygen past this amount (Figure 3), often up to 60 of 80 liters per minute. At flow rates above 15 LPM, you will not be able to precisely control the flow (nor the FiO2), but you can deliver more oxygen than typically delivered with conventional therapy and more closely match the minute ventilation of the patient. This can be used as a bridge to intubation or noninvasive ventilation,14,15 but should not be utilized for long-term use as the equipment is not designed for the high flow of gas that you are putting through it. The lack of warming and humidification can also be irritating to the upper airway mucosa. Be sure to firmly attach the cannula or NRB mask to the regulator, otherwise it will pop off and make a ferocious noise that will terrify everyone in the room.

Paul S. Jansson, MD, MS, is the medical director of the emergency critical care center (EC3), director of operations for the division of critical care, and an assistant professor of emergency medicine and internal medicine at the University of Michigan.

Paul S. Jansson, MD, MS, is the medical director of the emergency critical care center (EC3), director of operations for the division of critical care, and an assistant professor of emergency medicine and internal medicine at the University of Michigan.

References

- Levitan RM. Avoid Airway Catastrophes on the Extremes of Minute Ventilation. ACEP Now. Published January 20, 2015. Accessed August 6, 2025. https://www.acepnow.com/article/avoid-airway-catastrophes-extremes-minute-ventilation/.

- Blackie SP, Fairbarn MS, McElvaney NG, Wilcox PG, Morrison NJ, Pardy RL. Normal values and ranges for ventilation and breathing pattern at maximal exercise. Chest. 1991;100(1):136–142.

- Warner MA, Patel B. Mechanical Ventilation. In Benumof and Hagberg’s Airway Management. Third Edition. Elsevier; 2013 981-997.e3.

- Herren T, Achermann E, Hegi T, Reber A, Stäubli M. Carbon dioxide narcosis due to inappropriate oxygen delivery: A case report. J Med Case Rep. Published July 28, 2017. Accessed August 6, 2025.https://jmedicalcasereports.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13256-017-1363-7.

- Seeger K. The complete guide to high flow nasal cannula therapy (HFNC). Hamilton Medical. Published December 6, 2024. Accessed August 6, 2025. https://www.hamilton-medical.com/en_US/Article-page~knowledge-base~efb4fa6e-cb67-4e7c-ac50-28b9e3472a04~The-complete-guide-to-high-flow-nasal-cannula-therapy–HFNC-~.html.

- Drake MG. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen in adults: An evidence-based assessment. Ann Am Thorac Soc. Published February 2018. Accessed August 7, 2025. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201707-548FR.

- Parke RL, Eccleston ML, McGuinness SP. The effects of flow on airway pressure during nasal high-flow oxygen therapy. Respir Care.2011; 56(8):1151–1155.

- Ni YN, Luo J, Yu H, et al. Can High-flow Nasal Cannula Reduce the Rate of Endotracheal Intubation in Adult Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure Compared With Conventional Oxygen Therapy and Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation?: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2017;151(4):764–775.

- Frat J-P, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. High-Flow Oxygen through Nasal Cannula in Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med.2015; [372(23):2185–2196.

- Besnier E, Guernon K, Bubenheim M, et al. Pre-oxygenation with high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation for intubation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med.2016; [42(8):1291–1292.

- Jaber S, Monnin M, Girard M, et al. Apnoeic oxygenation via high-flow nasal cannula oxygen combined with non-invasive ventilation preoxygenation for intubation in hypoxaemic patients in the intensive care unit: the single-centre, blinded, randomised controlled OPTINIV trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42(12):1877–1887.

- Miguel-Montanes R, Hajage D, Messika J, et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy to prevent desaturation during tracheal intubation of intensive care patients with mild-to-moderate hypoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):574–583.

- Robinson AE, Pearson AM, Bunting AJ, et al. A Practical Solution for Preoxygenation in the Prehospital Setting: A Nonrebreather Mask with Flush Rate Oxygen. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2024;28(2):215–220.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Kornas RL, Cales EK, Reardon RF. Flush Rate Oxygen for Emergency Airway Preoxygenation. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(1):1–6.

- Bunting AJ, Driver BE, Pearson AM, et al. Time to adequate preoxygenation when using flush rate oxygen. AmJ Emerg Med.2025;95:63–66.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Why the Nonrebreather Should be Abandoned”