Procedural sedation and emergency airway management are recognized risks to patient safety. Sedation, induction agents, and muscle relaxants can quickly impact oxygen saturation, and desaturation is often precipitous.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 04 – April 2018What contributes to the sorcery that seems to surround airway management and procedural sedation, and how can we avoid bad outcomes?

Gas Monitoring

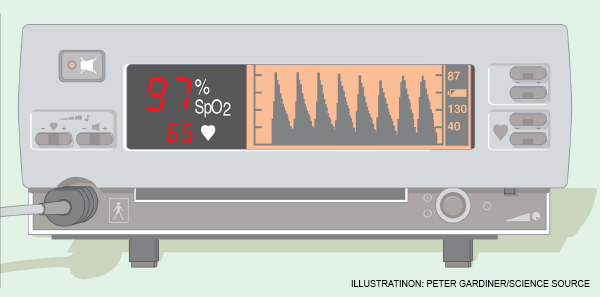

First, recognize that with pulse oximetry, we use an imperfect monitor. It lags what’s happening in your patient by 30–90 seconds. Moreover, it does not give you an estimation of safe apnea time, even with high values (ie, 94–100 percent), because the asymptotic shape of the pulse oximeter curve displays saturation, not the amount of oxygen in the blood (ie, the partial pressure of O2 [PaO2] in a blood gas). A pulse oximeter reading of 95 percent may represent a PaO2 of 80, while a pulse oximeter reading of 100 percent can represent a PaO2 of anywhere from 95–600 (see Figure 1).

The argument for CO2 monitoring is that it monitors ventilation and therefore is immediate as well as forward looking. The problem: Most commonly used end-tidal CO2 detection methods (ie, small bore nasal cannulas) can’t provide higher flows (ie, >6 lpm) without popping off the oxygen source. Even if you rig a cannula or other mechanism to place the CO2 detector into or under a mask, high-flow oxygen given simultaneously affects CO2 detection.

Figure 2: A standard nasal cannula, shown here, can be paired with a with a low-flow cannula with end-tidal CO2 detection to avoid affecting CO2 detection when higher flows are needed.

PHOTO: Richard Levitan

Perhaps the easiest way around this is to use two cannulas—that is, start with a low-flow cannula with end-tidal CO2 detection, and if you need higher flows, run oxygen through a standard nasal cannula previously placed on the patient (see Figure 2). Coming off the wall, a standard nasal cannula can deliver flows well above 50 lpm (even though the manometer only goes to 15 lpm) and as high as 70 lpm. “O’s up the nose” at these high flows can dramatically improve oxygenation, assuming the airway remains patent.

Divide the Airway

After more than twenty years of being airway obsessed, I recently began to gain a different perspective of the anatomy and clinical challenges of airway management. I believe it is useful to divide the airway into three sections to improve our anatomic understanding, and more importantly, to guide therapeutic intervention (see Figure 3):

- The upper airway includes the nasopharynx, mouth, and the hypopharynx down to the larynx. The upper airway is the most common site of airway obstruction due to the soft tissue structures of the palate, tongue, and epiglottis.

- The middle airway runs from the laryngeal cartilages (larynx) to the bronchi. It is normally patent, stented open by the rigidity of the thyroid and cricoid cartilage, and the tracheal rings.

- The lower airway includes the lungs and alveoli, where gas absorption occurs across the alveolar-capillary membrane.

To decipher the sorcery of the airway, we must appreciate how sedation, positioning, and our therapeutic interventions and techniques affect the airway at all three levels. Gravity is the enemy of both upper and lower airway patency when the patient is in a supine position. Supine positioning (coupled with poor muscular tone) causes the tongue to fall backwards against the soft palate and contact the posterior pharynx. Oral airways and/or nasopharyngeal airways are often needed to keep the soft palate and tongue from obstructing the airway. This is problematic because some patients may have respiratory depression or poor tone, but an oral airway may still trigger a gag response and vomiting, risking aspiration. Although mask ventilation techniques emphasize jaw thrust, struggling to maintain upper airway patency in a supine position is intrinsically self-defeating. It is also ergonomically difficult and frequently a multi-person task, especially in large patients.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Tips to Improve Airway Management”