Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 05 – May 2023FIGURE 3: Coronal CT lung window of subcutaneous air (red arrows), chest wall defect (white arrow).

Trauma labs were notable for a lactate of 3.0 mmol/L and a serum ethanol level of 160 mg/dL.

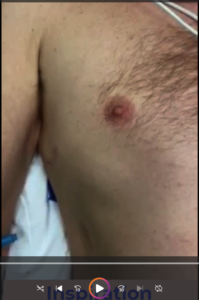

On re-evaluation, the chest wall movement was noted not to be following the paradoxical movement typical of flail segments. Instead, the flail segment was bulging outward with both inspiration and expiration (see Figure 4 video). The trauma team placed a pigtail catheter in the right chest cavity to decompress the pneumothorax and the patient was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit.

The patient continued to have an oxygen requirement and significant pain. On hospital day 2, he was taken to the operating room for surgical rib fixation. A chest tube was placed at that time. On postoperative day 5, the chest tube was removed, and he was discharged the following day (Figure 5).

Discussion

Displaced rib fractures can injure lung tissue and cause a pneumothorax. In this case, the patient’s pneumothorax was decompressed into a large soft tissue defect in his chest wall. The extensive chest-wall disruption resulted in soft tissue emphysema that was bulging with respirations mimicking a flail chest. A flail chest is defined by multiple fractures in three or more consecutive ribs with paradoxical movement of the resulting chest wall segment. Flail chest can result in respiratory failure. Initial management includes analgesia and positive pressure ventilation to help stabilize the chest wall.1 Unlike the typical paradoxical chest wall movement seen with flail chest, the subcutaneous tissues in this case were inflating with both inspiration and expiration although this was not fully appreciated due to the significant discomfort the patient experienced when the splint was removed. The direct movement of air into the chest wall was improved with the placement of a pigtail catheter and ultimately treated with operative repair.

FIGURE 5: Chest X-ray OF post open reduction and interior fixation of rib fractures. (Click to enlarge.)

Traditionally, treatment of flail chest was aimed at associated injuries, especially pulmonary contusions, and supportive care. Definitive treatment with surgical stabilization has been gaining favor, with current literature suggesting decreased ICU stays and fewer complications, especially with patients under 60 years old when taken to the operating room within 72 hours of injury.2

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Case Report: EMS Says Flail Chest, But Is It?”