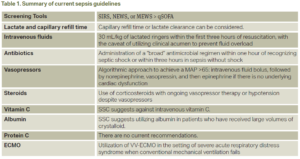

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction secondary to a dysregulated host response to an infection; an estimated 48.9 million cases are recorded, and 11.0 million sepsis-related deaths were reported from 1990-2017.1 From its first definition in 1991, many landmark trials have advanced the care of sepsis and septic shock. In 2001, Rivers and colleagues found that early intravenous fluid administration may improve overall in-hospital mortality rates.2 Similarly, in 2004, Kumar and colleagues demonstrated that each hour of delay in administration of antibiotics may lead to a mean decrease in survival.3 From there, multiple studies have investigated vasopressor use, corticosteroids, and even vitamin C in the establishment of an effective set of guidelines in the management of severe sepsis and septic shock. The predominant entity regulating the policies regarding sepsis management is the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC). Secondary entities, such as Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, require sepsis bundle timeline cut-offs for a health care entity to receive reimbursement. Despite many years of sepsis research, physicians still receive continuous updates suggesting new strategies to increase overall survival and decrease mortality in this patient population. A summary of these recommendations can be found in Table 1.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 06 – June 2024What Is “Sepsis”?

In sepsis, a pathogen triggers an initial exaggerated inflammatory-immune response that leads to activation or suppression of multiple pathways, in turn leading to circulatory and metabolic dysfunction.4 The clinical definition of sepsis is the recognition of two SIRS criteria with evidence of infection. Severe sepsis is defined as sepsis with evidence of organ dysfunction. One result of this dysregulated response is hemodynamic instability despite fluid resuscitation, ultimately classified as “septic shock,” which persistently remains a significant cause of mortality.5

What Can I Do to Combat Sepsis in 2024?

1. Screening tools

Multiple screening tools in the emergency department (ED) have been studied, including qSOFA, SIRS, NEWS, and MEWS. Sepsis-3 first considered the qSOFA score to be the superior screening tool to utilize in early sepsis identification.6 The SSC guidelines for 2021 recommend against the use of qSOFA when compared to SIRS, NEWS, or MEWS.7 A more recent study compared SIRS (body temperature above 38°C or below 36°C, heart rate greater than 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute, neutrophilia above 12,000 mm3 or below 4000 mm3) and qSOFA (systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg, respiratory rate >22, and Glasgow coma scale <15) to a Sepsis Prediction Model, which generates a sepsis score based on electronic health record-confirmed sepsis; however, its application in the clinical setting was limited by poor timeliness in comparison to SIRS and qSOFA.8

One Response to “Updates in the Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock”

July 1, 2024

Joseph R Shiber, MDDear ACEPNow Editor,

Excellent synopsis of ED treatment of septic shock but I would like to add a few clarifications. The preferred balanced IVF is Plasmalyte-A since LR is somewhat hypotonic (Na 130) and uses lactate as a buffer, compared to acetate and gluconate in Plasmalyte-A (Na 140). The additional lactate is not actually detrimental to cellular activity but can hamper the usefulness of tracking lactate levels especially with hepatic or mitochondrial dysfunction where lactate is not being converted back to pyruvate for preparation to enter the TCA cycle. The optimal vasopressor for septic shock should correct the hemodynamic disorder(s) causing the tissue hypoxia. Levophed is certainly the most useful to help restore vascular tone (alpha effect) in the low SVR vasodilatory state of distributive shock while supplying a small B1-2 effect but there are cases where an inappropriate heart-rate response occurs (HR <80) due to medications (such as AVN blockers) or to intrinsic chronotropic failure (age or sepsis related). In these cases, it is paramount to address the heart rate at the same time, since if the heart rate remains inappropriately low while simply increasing SVR the cardiac output and tissue perfusion will potentially go down not up. Lastly, although ECMO is well recognized as a rescue for ARDS (V-V) and circulatory shock (V-A) it should be noted that active bacteremia or fungemia is a contraindication since the circuit will be contaminated immediately and cannot be sterilized.

Respectfully,

Joseph Shiber, MD, FACEP, FACP, FNCS, FCCM