Pain management of the acutely injured patient with rib fractures can be difficult for even the most experienced emergency physician. Severe pain from multiple rib fractures (or even one) can impair ventilatory function, decreasing the ability to clear respiratory secretions and increasing rates of nosocomial pneumonias.1,2 A multimodal approach to pain control via intravenous medications (eg, opioids, ketamine, acetaminophen, etc.) is reasonable but often insufficient. Epidural analgesia, recommended strongly by trauma guidelines for patients with multiple rib fractures, is often not acutely available in the emergency department. An opioid-sparing multimodal approach that integrates regional anesthesia is believed to be optimal for patients.3 Alternatives such as intercostal blocks are time-intensive, involve multiple injections, are often more difficult to perform, and necessitate patient repositioning.4 The ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) is a promising single-injection method to anesthetize the chest wall in patients with multiple rib fractures, providing optimal emergency department care.1

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017Anatomy and Innervation

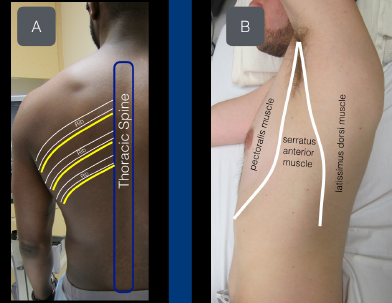

Figure 1A: View of the thoracic intercostal nerves as they exit the spine inferior to the ribs.

Figure 1B: The serratus anterior muscle sits between the pectoralis muscle (anterior) and latissimus dorsi muscle (posterior).

The chest wall is innervated from the lateral cutaneous branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves (T2–T12). The thoracic intercostal nerves run with the intercostal artery and vein, just under the rib, traveling in an anterolateral direction. As the thoracic intercostal nerve reaches the midaxillary line, the lateral cutaneous branch of the intercostal nerve pierces the internal intercostal muscle, external intercostal muscle, and serratus anterior muscle to innervate the musculature of the thorax. The serratus anterior muscle is a

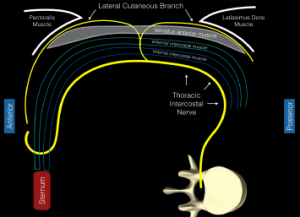

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the intercostal nerves as they travel from the thoracic spine. The distal lateral cutaneous branch exits at approximately the midaxillary line and pierces the internal intercostal muscle, external intercostal muscle, and serratus anterior muscle. The anterior fascial plane above the serratus anterior muscle acts as the target for this planar block.

readily visualized sonographic landmark, located posterior to the lateral edge of the pectoralis muscle and anterior to the lateral edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle (see Figures 1A and 1B). The distal branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves (lateral cutaneous intercostal nerves) provide innervation to the lateral thoracic cage and lie in the fascial plane just superficial to the serratus anterior muscle (see Figure 2). Placing large-volume dilute anesthetic solution into this potential space (formed by the serratus anterior muscle) is theorized to spread in a cephalad and caudal direction with patient respirations, providing analgesia for thoracic injuries (and specifically rib fractures).5

Supplies

- High-frequency linear transducer (13–6 MHz)

- Anesthetic: 15 mL bupivacaine 0.5% (5 mg/mL; maximum 2 mg/kg) and 15 mL normal saline placed in a 30 mL syringe (note: in patients under 40 kg, please be aware of the need to lower the volume of anesthetic)

- 22 g blunt-tip block needle or 20–22 g Quincke spinal needle

- 91 cm or 36″ tubing (or similar tubing)

- Cleaning solution

- 25–30 g needle for local skin wheal

Because of the large volume of dilute anesthetic planned to be deposited in the fascial plane above the serratus anterior muscle, we recommend a two-provider technique. In a 30 mL syringe, place a mixture of 15 mL 0.5% bupivacaine and 15 mL normal saline. Connect the needle to the tubing and prime the circuit to ensure all air is removed.

Procedure

1. Pre-block.

Whenever performing an ultrasound-guided nerve block, we recommend the patient be placed on continuous cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. Also, the operator should be aware of the possibility of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST). The clinician should know the availability of 20% lipid emulsion therapy and dosing (lipidrescue.org).

2. Survey scan.

Moving acutely injured trauma patients is often not possible. In our experience, the following two patient positions have allowed for successful SAPB in all of our acutely injured patients.

Position 1: Lateral decubitus. Roll the patient in a lateral decubitus position (contralateral to the injury). If possible, ask the patient to place a hand behind the head.

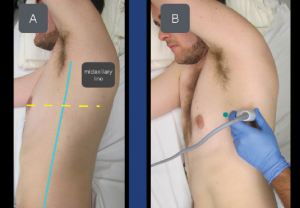

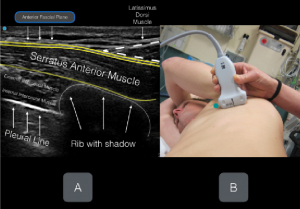

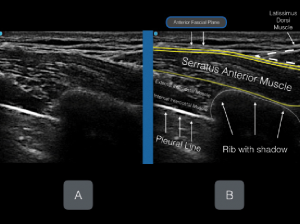

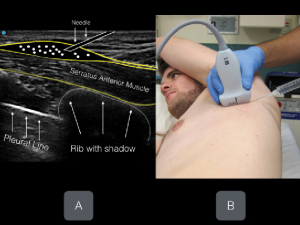

Place a high-frequency linear transducer in the transverse plane (probe marker facing the nipple) at the level of the fifth rib (surface anatomy = approximately at the level of nipple) in the midaxillary line (see Figures 3A and 3B). Ultrasound landmarks that will be easily recognized by clinicians with some chest sonography experience include the hyperechoic ribs (anechoic shadow) and the pleural line. Find these basic landmarks first and then slowly attempt to locate the more superficial soft tissue structures. The serratus anterior muscle (flat and elongated) lies just superficial to the ribs, with the intercostal muscles deeper and in between the bony ribs. The latissimus dorsi muscle will be seen superior and posterior to the serratus anterior muscle and can act as a nice landmark (see Figures 4A and 4B and Figures 5A and 5B).

Figure 3A & B: To locate the serratus anterior muscle, place the transducer at the level of the nipple in the midaxillary line. The transducer marker (green dot) should point toward the nipple.

Figures 4A & B: Labeled ultrasound image with corresponding transducer positioning. Note the anterior fascial plane of the serratus anterior muscle. The goal of the planar block is to place anesthetic in this fascial plane.

In some patients, a slight clockwise rotation of the transducer will allow for an improved cross-sectional view of the ribs and the pleural line.

Position 2: Supine. The SAPB can be performed with the patient in a supine position as well and may be ideal in cases of multi-trauma or cervical spine injury or when the lateral decubitus position is not tolerated.

Place the transducer in the midaxillary line (probe marker facing the nipple) and locate the ribs (anechoic shadow), pleural line, and serratus anterior muscle (as above). The latissimus dorsi muscle may not be clearly visualized with the transducer in the more anterior position. Again, the fascial plane located on top of the serratus anterior muscle will be the target for anesthetic deposition.

Figures 5A & B: Unlabeled (A) and labeled (B) ultrasound image.

Figures 6A & B: Anesthetic deposition in the anterior fascial plane above the serratus anterior muscle.

3. Skin wheal.

After cleaning the area under and around the transducer, place an anesthetic skin wheal (3–5 mL lidocaine with epinephrine) posterior to the transducer with the patient in a lateral decubitus position and anterior to the transducer with the patient in supine position. Clean the area and apply a transparent dressing over the transducer.

4. Needle entry.

Inject the skin wheal with an in-plane approach, always noting the needle tip. Once the visualized needle tip is located just above the serratus anterior muscle, aspirate to confirm lack of inadvertent vascular puncture and slowly inject 1–2 mL of anesthetic solution. Fluid placed in the fascial plane will immediately spread away from the needle tip and open the fascial plane. Anesthesia placed incorrectly in the serratus anterior muscle will not separate the fascial plane. Once the fascial plane is clearly opened, aspirate, then gently inject 2–3 mL of dilute anesthetic solution in a sequential manner until all 30 mL of dilute anesthetic is injected (see Figure 6). Ensure clear needle-tip visualization and lack of inadvertent vascular puncture during deposition of the entire dilute anesthetic volume. Clinicians should be aware that onset of analgesia is often longer for planar blocks; expect 15–30 minutes before onset of the block.

Unlike other nerve blocks that are classically thought to target a single nerve, the goal of the ultrasound-guided SAPB is to deposit a large volume of dilute anesthetic in a fascial plane. Anechoic anesthetic fluid will slowly spread with patient respirations and anesthetize the interconnected lateral cutaneous branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves.

Summary

Acute pain control in the emergency department for patients with multiple rib fractures can be a conundrum. A multimodal pain strategy that centers around the ultrasound-guided SAPB could offer significant pain relief without altering sensorium or respiratory drive. This ultrasound-guided planar block could alter the classic, and often ineffective, algorithm for the treatment of patients with acute rib fractures in the emergency department while maintaining vital pulmonary function.

Dr. Nagdev is director of emergency ultrasound at Highland Hospital, Alameda Health System, in Oakland, California

Dr. Mantuani is assistant director of emergency ultrasound at Highland Hospital.

Dr. Durant is an ultrasound fellow at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

Dr. Herring is associate research director at Highland Hospital.

References

- Durant E, Dixon B, Luftig J, et al. Ultrasound-guided serratus plane block for ED rib fracture pain control. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(1):197.e3-197.e6.

- May L, Hillermann C, Patil S. Rib fracture management. BJA Education. 2016;16(1):26-32.

- Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Clas D, et al. Elderly trauma patients with rib fractures are at greater risk of death and pneumonia. J Trauma. 2003;54(3):478-485.

- Karmaker MK, Ho AM. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured rib. 2003;54(3):615-625.

- Blanco R, Parras T, McDonnell JG, et al. Serratus plane block: a novel ultrasound-guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anesthesia. 2013;68(11):1107-1113.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

6 Responses to “Ultrasound-Guided Serratus Anterior Plane Block Can Help Avoid Opioid Use for Patients with Rib Fractures”

April 3, 2018

Santi Di PietroCongratulations for the article! Clear and complete… how should I cite it in a scientific research?

Sincerely

Santi Di Pietro

Junior EM Resident,

University of Pavia

April 9, 2018

Dawn Antoline-WangThe citation for this article is:

Nagdev A, Mantuani D, Durant E, Herring A. The ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block. ACEP Now. 2017;36(3):12-13.

August 14, 2018

Jonathan CheungIs this plane block effective as a one-off procedure or do you often need to repeat it later?

May 9, 2020

Dr.S.RadhakrishnaThank you for this useful article. The figure 2 shows the vertebra pointing in the wrong direction. The spinous process should point posteriorly and the body anteriorly. An error?

March 23, 2021

Dr Maya DehranThanks for sharing the very useful simple technique to treat the severe pain of chest injury.

January 18, 2022

DAVID CAMPELL, MDHow long does this block last before it has to be repeated to maintain pain control?