The Problem

A cervical artery dissection (CAD) occurs when a tear in the intima of a carotid or vertebral artery initiates a dissection along the length of the artery. An intramural hematoma with subintimal dissections may develop, resulting in stenosis of the artery and potentially complete occlusion and/or showering of emboli distally. Symptoms result from both local vessel distension and clot as well as downstream hypoperfusion. CAD is a relatively common cause of ischemic stroke in young people and has recently become more prevalent, largely owing to improved access to CT angiography and advances in neuroimaging.1 Despite these trends, CAD is likely underdiagnosed.2

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 02 – February 2022Why do we often miss CAD on the initial visit to the emergency department? There are several reasons. First, some patients present with pain in the head and/or neck as their only symptoms.3 Second, ischemic stroke symptoms, which occur in approximately two-thirds of patients, may be delayed for as long as two months.4 Third, if neurological findings are present, they may be transient or fluctuating and do not necessarily fit a typical large-vessel occlusion pattern. The median time to diagnosis from onset of symptoms is seven days, so it is commonly missed on initial presentation to the emergency department.3

This article aims to enhance your understanding of CAD so that you are more likely to pick it up without excessive use of CT angiography.

Arriving at a Pretest Probability

Arriving at a pretest probability for CAD high enough to trigger obtaining advanced neuroimaging should involve an assessment of risk factors. These include connective tissue disorders such as Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, recent infection, history of migraine headaches, oral contraceptive pill use, smoking, and the peripartum period.5,6 Importantly, ruling in a diagnosis of migraine headache does not necessarily rule out a diagnosis of CAD. While recent chiropractic manipulation of the neck has been shown to be associated with CAD, a causal role has never been proven.7 While observational data suggest that 80 percent of CADs are preceded by trauma, it is difficult to implicate minor trauma such as shaving the neck or extending the neck to replace a light bulb in a ceiling as the cause.7 Regardless, it is reasonable to ask patients who present with unusual head and/or neck pain if they have incurred any recent minor trauma to the head or neck.

Manifestations: Local and Downstream

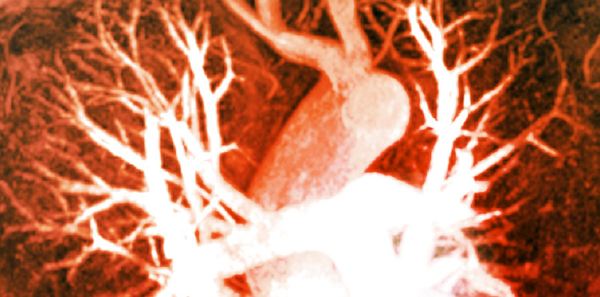

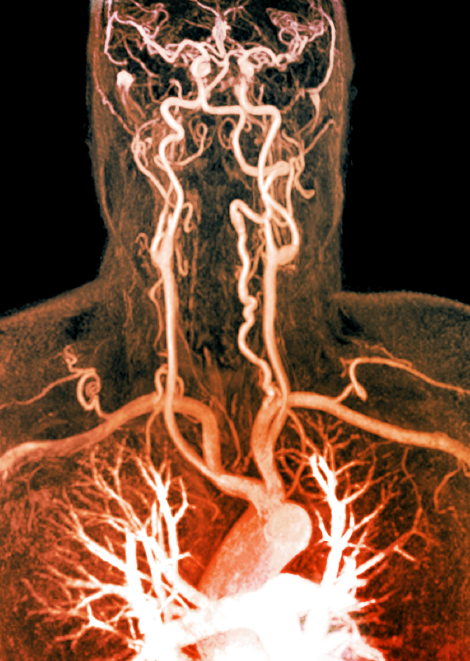

ZEPHYR/Science Source

The clinical manifestations of CAD can be divided into local phenomena and downstream phenomena. The hallmark of CAD is neck pain and/or headache, which occurs in 74 percent of cases, is often severe, and may be migrating in nature.8 This corresponds to the tear in the intima and dissection along the artery. The onset of pain may be “thunderclap” in nature, hence mimicking a subarachnoid hemorrhage. It is therefore important to consider CAD as the cause of an abrupt-onset headache after a negative workup for subarachnoid hemorrhage, as plain CT and lumbar puncture are likely to be normal in patients with CAD without obvious central nervous system (CNS) ischemic symptoms. The pain may also come on more gradually, be intermittent, or fluctuate.

Neurological symptoms, if they occur, most often occur within the first 24 hours.1 Local neurological symptoms caused by local stretching, distention, and clotting of the artery may include a partial Horner’s syndrome.9 As such, it is important to carefully examine patients in whom you suspect the diagnosis for ptosis and miosis. Other local manifestations include cranial neuropathies and pulsatile tinnitus, and if the dissection extends into the intracranial vault, subarachnoid hemorrhage may occur.10

Downstream phenomena depend on whether the dissection is in the vertebral or carotid artery. It is important to realize that while carotid dissections generally cause contralateral neurological findings, vertebral dissections may cause contralateral or bilateral findings. While classic middle cerebral, anterior cerebral, or posterior cerebral artery territory stroke syndromes may occur, a variety of seemingly nonanatomical neurological findings may manifest because of showering of emboli distally. Vertebral artery dissection may rarely present with isolated vertigo, although a careful examination for long-tract signs and the classic “D’s” of posterior circulation stroke (diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, dystaxia) usually reveals an abnormality that should trigger a search for CAD in the young patient with vertigo.11,12

CAD may present with a variety of local and downstream phenomena that may be delayed from the onset of pain, may be fluctuating or transient, and may seemingly not fit a classic anatomical vascular distribution, making the diagnosis especially difficult.

When to Use CT Angiogram of the Head and Neck

Based on risk factor assessment, detailed questioning of the headache or neck pain characteristics, and any neurological findings discovered on examination, if your pretest probability is more than one to two percent for the diagnosis of CAD, it would not be unreasonable to pursue the diagnosis by first ruling out an intracranial bleed with noncontrast CT and then confirming the diagnosis on CT angiogram of the head and neck. MRI with contrast is the gold standard for diagnosis, but it is seldom accessible in a timely manner for most emergency physicians.13

Management of CAD

There is no high-level evidence for clinical benefit for any treatment strategies for cervical artery dissections.

Emergency department management of CAD starts with attention to the ABCs and other considerations for stroke patients including blood pressure management, glucose control, etc. I find it useful to divide patients into three groups for management decisions:

- Group 1: Those with a suspected diagnosis but who have not yet had advanced neuroimaging to confirm the diagnosis

- Group 2: Those with imaging-confirmed extracranial dissections

- Group 3: Those with imaging-confirmed intracranial dissections

For those patients who have not had their diagnosis of spontaneous CAD confirmed by CT angiogram of the head and neck, some recommend treating on speculation with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) [personal correspondence].14 However, there is no evidence to suggest that this practice significantly improves outcomes, and if the patient is later found to have an intracranial dissection with subarachnoid hemorrhage, ASA may lead to further bleeding.

While CAD is commonly treated with anticoagulants such as low-molecular-weight heparin, two sizable trials, the CADISS trial and the TREAT-CAD trial, comparing antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants have failed to show a clinically meaningful significant difference in outcomes of recurrent stroke or death.15,16 Other prospective observational studies have suggested that those treated with anticoagulants had fewer one-year recurrent events than patients treated with antiplatelet agents; however, there was no statistically significant difference.17

Both endovascular and systemic thrombolysis have been studied; however, there are no randomized controlled trials to support their use, and observational studies show no clinical benefit, with an increase in intracranial hemorrhage.18 Endovascular stenting has also failed to show significant clinical benefit.19 Given the clinical equipoise in the literature with all treatments for CAD, consultation with your local neurologist upon diagnostic confirmation will help to guide management.

Next time you are faced with a young patient with an unusual new-onset headache and/or neck pain, consider the diagnosis of CAD. If your pretest probability for the diagnosis based on risk factor assessment and any new, transient, fluctuating or permanent local neurological or CNS manifestations is more than 1 to 2 percent, consider workup with noncontrast CT of the head to rule out an intracranial bleed followed by a CT angiogram of the head and neck. If the diagnosis of CAD is confirmed, involve your neurology colleagues for management decisions, as the literature is not clear as to the most effective treatment. CAD is sometimes a very difficult diagnosis to make on an initial visit to the emergency department; by increasing your awareness and clinical suspicion for this rare disease, you will be less likely to miss this diagnosis.

References

- Morris NA, Merkler AE, Gialdini G, et al. Timing of incident stroke risk after cervical artery dissection presenting without ischemia. Stroke. 2017;48(3):551-555.

- Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906.

- Arnold M, Cumurciuc R, Stapf C, et al. Pain as the only symptom of cervical artery dissection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1021-1024.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Guillon B, Berthet K, Benslamia L, et al. Infection and the risk of spontaneous cervical artery dissection: a case-control study. Stroke. 2003;34(7):e79-81.

- Shea K, Stahmer S. Carotid and vertebral arterial dissections in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2012 Apr;14(4):1-23.

- Biller J, Sacco RL, Albuquerque FC, et al. Cervical arterial dissections and association with cervical manipulative therapy a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(11):e261.

- Norris JW, Beletsky V, Nadareishvili ZG. Sudden neck movement and cervical artery dissection. The Canadian Stroke Consortium. CMAJ. 2000;163(1):38-40.

- Mayer L, Boehme C, Toell T, et al. Local signs and symptoms in spontaneous cervical artery dissection: a single centre cohort study. J Stroke. 2019;21(1):112-115.

- Baumgartner R, Bogousslavsky J. Clinical manifestations of carotid dissection. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2005;20:70-76.

- Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012;18(5):245-254.

- Savitz SI, Caplan LR. Vertebrobasilar disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(25):2618-2626.

- Ben Hassen W, Machet A, Edjlali-Goujon M, et al. Imaging of cervical artery dissection. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95(12):1151-1161.

- Helman, A. Shah, A. Baskind, B. Episode 161 Red Flag Headaches: General Approach and Cervical Artery Dissections. Emergency Medicine Cases. November 2021. Accessed Jan 24th, 2022.

- Markus HS, Levi C, King A, et al. Antiplatelet therapy vs anticoagulation therapy in cervical artery dissection: the Cervical Artery Dissection in Stroke Study (CADISS) randomized clinical trial final results. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(6):657-664.

- Engelter ST, Traenka C, Gensicke H, et al. Aspirin versus anticoagulation in cervical artery dissection (TREAT-CAD): an open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(5):341-350.

- Beletsky V, Nadareishvili Z, Lynch J, et al. Cervical arterial dissection: time for a therapeutic trial? Stroke. 2003;34(12):2856-2860.

- Lin J, Sun Y, Zhao S, et al. Safety and efficacy of thrombolysis in cervical artery dissection-related ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;42(3-4):272-279.

- Sultan S, Hynes N, Acharya Y, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of carotid surgery and endovascular carotid stenting versus best medical treatment in managing symptomatic acute carotid artery dissection. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(14):1212.

Pages: 1 2 | Single Page

No Responses to “The Many Faces of Spontaneous Cervical Artery Dissection”