Unfortunately, the terms diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) now carry a host of negative connotations, signaling anything from undeservedness or lesser quality to incompetence and other pejoratives. In medical training, we are all sure to learn the names of Alexander Fleming or Jonas Salk. From the work of Hippocrates to that of Michael Ellis DeBakey, medicine prides itself on its history, and we strive to document it. Yet, how many physicians are familiar with buildings and institutions named after Daniel Hale Williams, Charles R. Drew, Rosalind Franklin, or Carlos Juan Finlay compared to the accomplishments of these trailblazers?

Explore This Issue

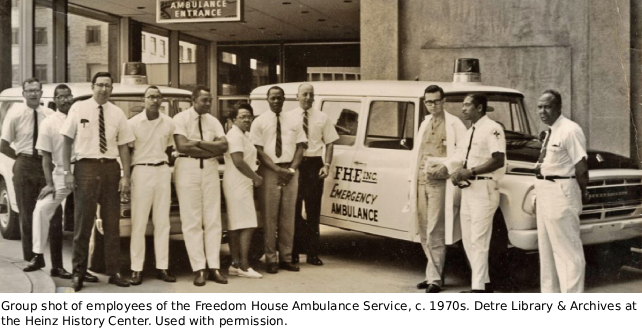

ACEP Now: February 2026 (Digital)I was humbled to discover the story of Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Ambulance Service not in a lecture hall, small group, clinic, conference, or textbook, but in an entertainment podcast called Stuff You Should Know.1 Freedom House was the first organized public emergency medical service in the United States, staffed by Black workers who were among the first Americans formally trained in out-of-hospital medicine. This group laid the groundwork for the modern EMS systems we rely on today.

That realization unsettled me. The protocols we take for granted were born from a deliberate investment in a marginalized workforce and community. To omit that context is to miss the deeper lesson: excellence in medical care and equity are not opposites but mutually reinforcing.

In 1966, the National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council published Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society, sounding a national alarm about the unacceptable state of out-of-hospital care in the United States.2 At the time, most ambulance crews were untrained, unregulated, and focused on rapid transport rather than providing any medical intervention.

In Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a predominantly Black neighborhood where disparities were especially stark, a coalition of activists, philanthropists, and physicians responded by founding the Freedom House Ambulance Service in 1967. Already renowned for his work in developing modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), Dr. Peter Safar designed the clinical framework for Freedom House, outfitting ambulances as mobile intensive care units. He was joined by Dr. Nancy Caroline, who developed the paramedic curriculum, served as the service’s first medical director, and later authored the first textbook for out-of-hospital care.

Freedom House’s origin story carried an explicit mandate: to modernize out-of-hospital care, to empower a marginalized workforce, and to serve an underserved community.

In 1967, the program recruited 25 men from Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Many of them were Vietnam War veterans, most were unemployed, and many were without a high school diploma. Once labeled “unemployables” by the city,these recruits entered a groundbreaking program that combined clinical rigor with social investment. 2 Over 32 weeks, they completed 300 hours of hospital-based instruction in anatomy, physiology, advanced first aid, CPR, ECG interpretation, defibrillation, and defensive driving. Alongside this training, they pursued GED coursework and life skills coaching, followed by nine months of supervised field internships in the Hill District and Oakland neighborhoods. This educational model was unprecedented; deliberately designed to build both workforce capacity and community trust.3

The results were transformative. Trainees moved from intermittent, low-skilled labor into salaried EMT roles, and many later earned degrees in nursing, public health, or medicine.3 Their skills proved transferable, opening doors to broader health careers and diversifying the health care workforce.4 Just as importantly, the presence of Black paramedics fostered trust: Residents who had once hesitated to call white-staffed police or funeral home ambulances embraced Freedom House crews, likely improving activation times and cooperation on scene.3

The clinical outcomes were impressive. In its first year, Freedom House operated five ambulances, responded to nearly 6,000 calls, and transported more than 4,600 patients, including 366 with life-threatening conditions.5 Data collected by Safar’s team estimated that more than 200 lives had been saved.4 Freedom House paramedics performed endotracheal intubation, administered intravenous medications, and transmitted ECG telemetry to receiving hospitals, interventions that were groundbreaking at the time but are now routine in out-of-hospital medicine.6

The curriculum later served as the foundation for the first national paramedic training standards and helped shape enduring protocols in United States EMS systems.6

By 1975, Freedom House was absorbed into Pittsburgh’s new citywide EMS bureau. Framed as a consolidation effort, the transition imposed written exams outside the Freedom House curriculum, reassigned crews, and disqualified individuals with prior criminal records. Within a year, only five of the original medics remained employed.

History is sobering. A system that had proven itself to be clinically excellent was dismantled under the guise of neutrality. The lesson is clear: Equity-driven innovation can transform care, but it can also be erased when policy shifts toward “colorblind” neutrality.

That lesson feels urgent now. Since January 2025, federal directives have dismantled DEI programs, banned race-conscious funding, and stripped equity language from health care mission statements. DEI offices have been shuttered across hospitals and universities.

For clinicians, the implications are immediate: fewer pathways for underrepresented trainees, less culturally concordant care, and the risk of returning to exclusionary practices that undermine trust and outcomes. The destruction of DEI infrastructure risks recreating the very conditions that necessitated Freedom House in the first place.

What can practicing physicians and health care professionals do in this climate? Freedom House offers a framework that remains strikingly relevant.

First, we must protect mentorship pipelines. Sponsoring trainees from diverse backgrounds and advocating for structured pathways in medicine are not abstract ideals, they are practical necessities. In my own experience, I have seen mentorship transform individuals once dismissed as “unemployables” into leaders.

Second, we should measure what matters. Equity-sensitive outcomes (e.g., activation times, patient trust, follow-up rates) must be tracked alongside traditional quality metrics. Numbers tell stories, and without them, inequities remain invisible.

Third, we must teach history. Incorporate historical lessons such as Freedom House into curricula not as a sidebar, but as an important case study in how equity and excellence reinforce each other. When I share this story with learners, they see that innovation is not only technical, but also social.

Fourth, we must model inclusive care. In daily practice, cultural humility, respect, and advocacy are as essential as technical skills. Freedom House succeeded because its crews embodied empathy as much as clinical competence.

Finally, we must publish and preserve. Equity-driven innovations must be documented and shared. We are fortunate that those who worked with Freedom House told their stories; in my own small way, I have tried to share them here.

Freedom House was not a nostalgic blip. It was a blueprint, showing that excellence in medicine can emerge from opening doors to those once excluded. As clinicians, we inherit that legacy.

I think often of the Freedom House medics, men once dismissed as “unemployables” who became pioneers of modern paramedicine. Their story reminds me that the most transformative changes in medicine can come from investing in those who have been ignored and daring to do what has never been done; that is, from thinking outside the box.

In a climate where equity is under siege, remembering Freedom House is more than history, it is a call to action for the profession of healers. If we fail to protect equity-driven pathways, we risk not only injustice but also the stagnation of clinical innovation.

Freedom House is not just a story. It is a standard. And it is ours to uphold.

References

- Clark J, Bryant J. Short Stuff: Freedom House Ambulance Services [podcast]. iHeartRadio; February 17, 2021. Accessed August 29, 2025. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-short-stuff-30006080/episode/freedom-house-ambulance-service-77875511/

- National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, Committee on Trauma and Committee on Shock. Accidental death and disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society. Washington, DC. National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council; 1966.

- Hazzard K. American Sirens: The Incredible Story of the Black Men Who Became America’s First Paramedics. New York: Hachette Books; 2022.

- Kellermann, A. America’s First Paramedics Were Black.Their Achievements Were Overlooked for Decades. Healthforce Center at the University of California San Francisco. 2022. Available at: https://healthforce.ucsf.edu/news/americas-first-paramedics-were-black-their-achievements-were-overlooked-decades. Accessed August 29, 2025.

- Corry M, Keyes C, Page D. Reviving Freedom House: How the storied ambulance company has been reborn. JEMS. 2013;38(3):70–75.

- Caroline NL. Medical Care in the Streets. JAMA. 1977;237:43–46.

No Responses to “The Historic Freedom House and the Future of Equity in Medicine”