Sleep is essential to life. The better we sleep, the better we concentrate, make decisions, and perform.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: September 2025Better sleep minimizes the chance of making errors on shift.1 Better sleep makes us learn better because it plays a key role in consolidating both declarative and procedural memory.2 Better sleep means better adaptive capacity to stressful situations, which are plentiful in emergency medicine.3

The better we sleep, the better mood we tend to be in and the better our relationships.4 The better we sleep, the lower our chance of developing cancer, heart disease, depression, and the longer we live—better sleep is associated with a decreased mortality rate!5 So, the better we sleep, the happier and healthier we are.

And, as we’re all too familiar with, shift work disturbs our wonderful sleep, because shift work interrupts our circadian rhythms and our sleep drive, leading to an increased risk for a motor vehicle crash on one’s commute home.6,7 In this column, I endeavor to provide you with some simple evidence-based strategies to improve your sleep architecture, minimize disruptions in circadian rhythm, and improve your sleep so that you can perform better on shift and improve your wellness and long-term health.

The Physiology of Sleep

Human sleep is governed by two primary physiologic processes: the homeostatic sleep drive (Process S) and the circadian rhythm (Process C).

Process S reflects the accumulation of adenosine in the brain during wakefulness, increasing the drive to sleep over time. This process accounts for the progressive sleepiness experienced after extended wakefulness or consecutive shifts.8 Process C is regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, which responds to environmental light cues—particularly blue-spectrum light—to synchronize the internal circadian rhythm to a roughly 24.2-hour cycle. Light exposure inhibits melatonin secretion via melanopsin-sensitive retinal ganglion cells, thereby promoting wakefulness.9

In contrast, darkness facilitates melatonin release and initiates sleep onset. Cortisol, a diurnal hormone, typically peaks 30–45 minutes after awakening, enhancing alertness during the daytime.10 Disruption of either Process S or Process C—as occurs frequently in shift work—results in impaired sleep duration, efficiency, and architecture. This disruption has both acute consequences (e.g., decreased vigilance, increased errors) and long-term sequelae (e.g., metabolic, psychiatric, and oncologic disease).11

Sleep Hygiene

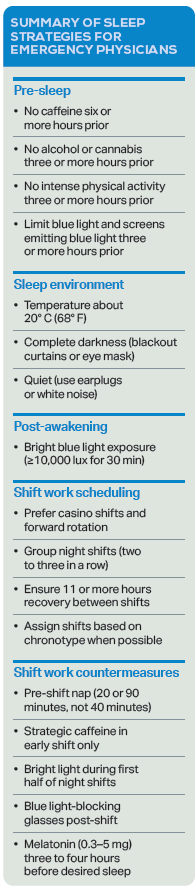

Optimal sleep hygiene includes interventions across three domains: pre-sleep behavior, sleep environment, and post-sleep routines. These recommendations are grounded in both circadian physiology and empirically supported behavioral strategies.12

Pre-sleep behavior: Avoid vigorous physical activity, cognitively stimulating tasks, and large meals for at least three hours before bedtime. These activities elevate core body temperature and sympathetic arousal, delaying sleep onset and reducing sleep efficiency.13,14

Caffeine, a competitive adenosine receptor antagonist, should be avoided for at least six hours prior to sleep initiation (or 12 hours in slow metabolizers). Daily intake should remain less than 400 mg.8 Alcohol, despite its sedative effects via GABAergic activation, disrupts sleep architecture through rebound arousal once metabolized.15 Similarly, chronic cannabis use reduces REM and slow-wave sleep, leading to fragmented sleep and long-term tolerance effects.16 Both substances should be avoided at least three hours before sleep.

Light exposure: Exposure to high-intensity, blue-spectrum light in the evening suppresses melatonin and delays sleep onset.9 Minimize screen use for at least three hours before bed. If screen use is unavoidable, use blue light filters or e-ink devices such as a Kindle. Light intensity should be minimized, and light sources should emit at lower Kelvin temperatures (e.g., 1,000–2,700 degrees Kelvin) to reduce circadian disruption. Consider using light bulbs that can switch to lower Kelvin temperatures three hours before sleep.17

Sleep environment: The ideal sleep environment is dark, cool (approximately 20° C or 68° F), and quiet. Use blackout curtains or a sleep mask to block ambient light and consider earplugs or white noise machines to mitigate environmental noise. Avoid visible clocks in the bedroom, as time-checking reinforces arousal and promotes sleep-onset anxiety.18

Post-waking routine: Morning light exposure—particularly blue-spectrum light at 10,000 lux for 30 minutes upon waking either by natural sunlight, by a light emitting screen or light emitting eye glasses—promotes circadian alignment and may enhance mood.19 This practice using artificial light is especially beneficial in regions with limited sunlight during winter months or in individuals with delayed sleep phase tendencies (e.g., adolescents and young adults).

Shift Work Adaptation

Several scheduling principles and physiological countermeasures can facilitate circadian alignment and performance optimization for emergency physicians engaged in shift work.

Shift scheduling: Casino shifts (e.g., 10 p.m.–4 a.m. and 4 a.m.–10 a.m.) preserve partial overnight sleep (anchor sleep), reduce circadian misalignment, and are less circadian disruptive than night shifts that start when it is dark outside and end when it is light outside.20 If casino shifts are not an option where you work, night shifts should be clustered, scheduled consecutively (two to three shifts maximum). Spacing night shifts throughout the month prolongs maladaptation and may increase performance deficits. Recovery time between shifts should be no less than 11 hours to allow adequate rest between shifts for peak performance on shift.21 Forward-rotating schedules (e.g., transitioning from evening to night to morning shifts) align with the natural tendency for phase delay and are preferred over backward rotations.22 Chronotype identification enables allocation of night shifts to naturally nocturnal individuals (evening types), minimizing circadian disruption and associated morbidity.23

Pre-shift preparation: Napping with knowledge of the sleep cycle is important. A 20-minute nap (before deep sleep kicks in), or a full 90-minute sleep cycle nap before a night shift can reduce sleep inertia and improve cognitive performance.24,25 However, napping for 30–60 minutes may cause increased fatigue because waking is generally during the phase of deep sleep. High-intensity cardiovascular exercise and caffeine ingestion 30–60 minutes prior to shift start can further enhance alertness.26-28 Limit caffeine intake to the first half of the shift to avoid impairing post-shift sleep onset.

During shift: Use of bright blue-spectrum light (10,000 lux) in the early part of night shifts enhances alertness without impairing subsequent sleep if exposure ceases at least two hours before sleep onset.9

Post-shift wind-down: Wearing blue-blocking glasses or dark sunglasses on the commute home reduces light-induced melatonin suppression. Supplemental exogenous melatonin (0.3–5 mg) taken three to four hours prior to the desired sleep onset may support circadian re-entrainment and improve sleep continuity. Doses greater than 5 mg confer no added benefit and may paradoxically disrupt sleep in some individuals.29

Pharmacologic Approaches

Although behavioral interventions should remain the first-line approaches, pharmacologic therapies may be necessary in select cases of shift work sleep disorder (SWSD).

Exogenous melatonin, as noted above, facilitates circadian entrainment with minimal side effects when properly timed. In more severe cases, short-acting, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (e.g., zolpidem, zopiclone) may aid with sleep initiation, although concerns regarding tolerance, dependency, and next-day sedation limit their long-term use.29

Wake-promoting agents such as modafinil and armodafinil have demonstrated efficacy in improving alertness and performance during night shifts in individuals diagnosed with SWSD.30,31 However, these agents may pose cardiovascular and psychiatric risks and should be reserved for refractory cases under specialist supervision.32

Cannabinoids, including THC and CBD formulations, are not recommended because of evidence of impaired sleep architecture, increased sleep fragmentation, and the potential for adverse psychiatric outcomes including psychosis.16

By implementing the outlined evidence-based strategies, emergency physicians can mitigate the adverse consequences of shift work, improve clinical performance, and protect long-term health. Sleep should not be viewed as expendable, but rather as an essential element of professional sustainability and patient safety.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of the Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

Dr. Helman is an emergency physician at North York General Hospital in Toronto. He is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, Division of Emergency Medicine, and the education innovation lead at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. He is the founder and host of the Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and website.

References

- Shriane AE, Rigney G, Ferguson SA, et al. Healthy sleep practices for shift workers: consensus sleep hygiene guidelines using a Delphi methodology. Sleep. 2023;46(12):zsad182.

- Newbury CR, Crowley R, Rastle K, Tamminen J. Sleep deprivation and memory: meta-analytic reviews of studies on sleep deprivation before and after learning. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(11):1215-1240.

- Vandekerckhove M, Wang YL. Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: an intimate relationship. AIMS Neurosci. 2017;5(1):1-17.

- Kent RG, Uchino BN, Cribbet MR, et al. Social relationships and sleep quality. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(6):912-917.

- Colten HR, Altevogt BM, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research, eds. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006.

- James SM, Honn KA, Gaddameedhi S, Van Dongen HPA. Shift work: disrupted circadian rhythms and sleep-implications for health and well-being. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2017;3(2):104-112.

- Lee ML, Howard ME, Horrey WJ, et al. High risk of near-crash driving events following night-shift work. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(1):176-181.

- Reichert CF, Deboer T, Landolt HP. Adenosine, caffeine, and sleep-wake regulation: state of the science and perspectives. J Sleep Res. 2022;31(4):e13597.

- Wahl S, Engelhardt M, Schaupp P, et al. The inner clock-blue light sets the human rhythm. J Biophotonics. 2019;12(12):e201900102.

- Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, et al. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;83:25-41.

- Boivin DB, Boudreau P, Kosmadopoulos A. Disturbance of the circadian system in shift work and its health impact. J Biol Rhythms. 2022;37(1):3-28.

- Baranwal N, Yu PK, Siegel NS. Sleep physiology, pathophysiology, and sleep hygiene. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;77:59-69.

- Shen B, Ma C, Wu G, et al. Effects of exercise on circadian rhythms in humans. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1282357.

- Iao SI, Jansen E, Shedden K, et al. Associations between bedtime eating or drinking, sleep duration and wake after sleep onset: findings from the American time use survey. Br J Nutr. 2021;127(12):1-10.

- Colrain IM, Nicholas CL, Baker FC. Alcohol and the sleeping brain. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;125:415-431.

- Kaul M, Zee PC, Sahni AS. Effects of cannabinoids on sleep and their therapeutic potential for sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18(1):217-227.

- Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(4):1232-1237.

- Tang NK, Anne Schmidt D, Harvey AG. Sleeping with the enemy: clock monitoring in the maintenance of insomnia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38(1):40-55.

- Blume C, Garbazza C, Spitschan M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie (Berl). 2019;23(3):147-156.

- Waggoner LB, Concannon TW, Darby MJ. Designing shift schedules for reduced fatigue and improved health outcomes. J Emerg Nurs. 2012;38(6):571-573.

- Dunbar M, Gray S. Shift work fatigue and medical errors: is 11 hours enough? CJEM. 2022;24(S1): S74.

- Di Muzio M, Diella G, Di Simone E, et al. Comparison of sleep and attention metrics among nurses working shifts on a forward- vs backward-rotating schedule. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2129906.

- Hittle BM, Gillespie GL. Identifying shift worker chronotype: implications for health. Ind Health. 2018;56(6):512-523.

- Boukhris O, Trabelsi K, Ammar A, et al. A 90 min daytime nap opportunity is better than 40 min for cognitive and physical performance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4650.

- Lovato N, Lack L. The effects of napping on cognitive functioning. Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:155-166.

- Hogan CL, Mata J, Carstensen LL. Exercise holds immediate benefits for affect and cognition in younger and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(2):587-594.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Marriott BM, eds. Food Components to Enhance Performance: An Evaluation of Potential Performance-Enhancing Food Components for Operational Rations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1994.

- Costello RB, Lentino CV, Boyd CC, et al. The effectiveness of melatonin for promoting healthy sleep: a rapid evidence assessment of the literature. Nutr J. 2014;13:106.

- Scharner V, Hasieber L, Sönnichsen A, Mann E. Efficacy and safety of Z-substances in the management of insomnia in older adults: a systematic review for the development of recommendations to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):87.

- Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, et al. Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift-work sleep disorder. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):476-486.

- Wickwire EM, Geiger-Brown J, Scharf SM, Drake CL. Shift work and shift work sleep disorder: clinical and organizational perspectives. Chest. 2017;151(5):1156-1172.

- Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(7):1477-1502.

No Responses to “Sleep Concepts, Strategies for Shift Work in the Emergency Dept.”