The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) was the nation’s first teaching hospital at the nation’s first medical school, now called the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. HUP had one of the earliest operating theaters, where surgeries were performed on sunny days between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m.—sunny days because there was no electricity. Some of the first anesthesia was delivered (whiskey and opium) to facilitate early surgical endeavors. Today, HUP remains prestigious, frequently rated among the top hospitals in the country and serving as a regional and national referral center.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 03 – March 2020And yet recently, the emergency department at HUP was struggling, as many hospitals do, with high boarding burdens. In 2018, the boarding burden exceeded 10,000 hours per month, translating into 16 lost beds in the 41-room emergency department, which was fielding 62,000 visits per year. Like many academic medical centers, HUP treats high-acuity patients.

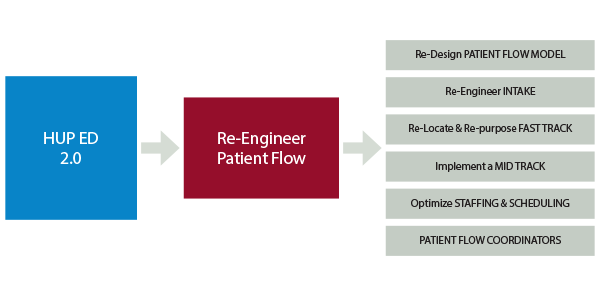

High boarding times were associated with unacceptable waits and walkaway rates. In 2019, the new chair of emergency medicine and his ED operations leadership team (representing nurses, advanced practice providers, and physicians) decided an overhaul was needed. With support from HUP executive leadership, the ED operations team decided to dismantle the old processes and implement a package of innovations that were dramatic and complementary (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ED Improvement Change Package

Building a Better Flow

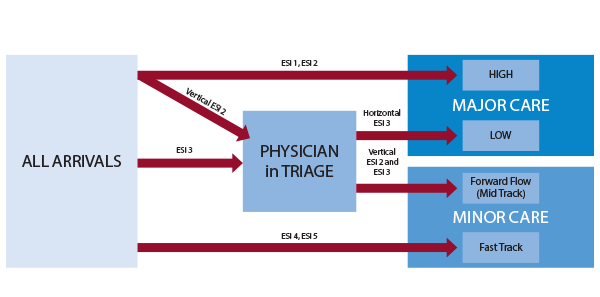

Because it was getting harder to populate a fast track and there were high volumes of intermediate-acuity patients, the ED leaders designed a custom flow model that allowed patients who could remain vertical to go to a mid-track-plus area known as Forward Flow. Unlike other mid-track models around the country, which see exclusively Emergency Severity Index (ESI) 3 patients, HUP developed inclusion criteria that allowed many ESI 2 patients to be treated safely in a lounge-like chair. For example, low-risk chest pain patients could be served in the vertical model. This allowed offloading of the ED acute care beds, the most precious real estate in the department. In fast track (only open on weekdays), advanced practice providers independently saw the lower-acuity patients.

The flow model designed for the HUP ED 2.0 Project is shown in Figure 2. This is one of the most complex streaming models we have seen, yet it perfectly adapted to the realities of the HUP emergency department. Patient segmentation allowed for the appropriate placement of patients into streams with similar acuities and clinical intensity. Each acuity-driven zone worked to optimize its efficiency and throughput.

Figure 2: HUP ED 2.0 FLOW MODEL

The HUP emergency department is a data-rich department, and it was able to manage each zone by studying zone-specific data. For each geographical zone, the leadership assessed:

- Appropriate streaming (mean ESI and admission rate)

- Productivity (daily volume and percent of volume)

- Efficiency (door-to-doctor time and length of stay)

The ED operations leadership team monitored each area and developed inclusion and exclusion criteria, time and volume targets, swim lanes delineating the roles of each person in the zone, and job description sheets for each role in each zone. This operational cleanup and standardization made it easier for everyone to know what was expected within each role.

The icing on the cake for the HUP ED 2.0 Project was the development of high-flow strategies. Department leaders identified early signs (triggers) that an area was becoming overwhelmed. Designated shift leaders (such as patient-flow coordinators, charge nurses, etc.) were trained to identify problems in a zone in real time, and for each high-flow situation, there was a short-term remedy. For instance, if the physician in triage was overwhelmed, creating a bottleneck, the Forward Flow (mid-track) attending physician would float to the triage area to help that physician get caught up. If a lab technician was behind, there might be backup.

The overarching theme in high-flow strategies is to have standardized and articulated trigger-response strategies mapped out in advance but activated in real time, deploying necessary personnel to an area to help the overwhelmed role in an overwhelmed zone.

High-flow strategies depend on physical layout, staffing models, and culture. As a result, they can be idiosyncratic to a particular emergency department. Many emergency departments attempt to manage high-flow situations with on-call arrangements, but that strategy is often not nimble enough. By the time an on-call physician or nurse is on scene, the crisis often has passed. The real-time strategies employed at HUP have been tried elsewhere but are not embedded into most emergency department operations.

Table 1: Metrics Before and After HUP ED 2.0 Implementation

| Metric | Baseline 2019 | First two months after go live |

|---|---|---|

| Daily volume | 168 | 183 |

| Boarding minutes | 342 | 457 |

| Admission rate | 29.9% | 30.8% |

| Door-to-doctor time | 81 | 25 |

| Length of stay (LOS) overall | 368 | 310 |

| LOS admitted | 690 | 741 |

| LOS discharged | 300 | 231 |

| LOS fast track | 169 | 118 |

| LOS mid track | NA | 240 |

| Walkaway total % | 8.9% | 3.6% |

The Results

The sum total of this sophisticated approach to ED operational challenges appears in Table 1. Door-to-doctor time fell by 70 percent, walkaways declined by 60 percent, and length-of-stay/discharged time dropped by more than an hour. These remarkable results were achieved despite several adverse headwinds, which included an overnight 9 percent volume increase (related to the closure of a nearby safety-net hospital), a 34 percent increase in boarding minutes (time from decision to admit to departure time), and an attending physician shortage (resulting from a 5 percent reduction in physician staffing).

HUP’s ED operations team continues to optimize the new flow model. But HUP ED 2.0 demonstrates the power of a multidisciplinary effort that combines creative problem-solving with data-driven decision making.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Pennsylvania ED Re-Engineers Patient Flow to Reduce Boarding Burden”