Looking back on my residency days, I have fond memories of calling for positive pressure ventilation (PPV) for a patient in respiratory distress, and confidently responding “10 over 5” when the respiratory therapist asked what settings I wanted. It was only after completing critical care fellowship that I realized that the respiratory therapist had actually been nodding knowingly at me, then proceeding to adjust the settings to what the patient actually needed. In this month’s column, I will aim to demystify the alphabet soup of PPV and add some tips and tricks from the intensive care unit.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: October 2025 (Digital)CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most basic mode of noninvasive PPV (NIPPV). CPAP involves the continuous application of a set level of positive pressure throughout the respiratory cycle, regardless of whether the patient is inhaling, exhaling, or even apneic. With CPAP, you generally have two variables to control: the level of CPAP (given in centimeters of water, or cmH2O), and the oxygen concentration (given as fraction of inspired oxygen, or FiO2) .1

CPAP is generally best for patients with oxygenation problems. Increasing the FiO2 raises the percentage of oxygen delivered, whereas increasing the level of CPAP raises the mean airway pressure and recruits more lung tissue to participate in gas exchange. Physiologically, as the level of CPAP is increased, intrathoracic pressure increases, causing a decrease in both preload and afterload, and an increase in recruited lung tissue, particularly for areas of atelectasis or pulmonary edema.2 Because of this physiology, it should be your first choice for patients with acute pulmonary edema.3-5

BiPAP

Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) is conceptually similar to CPAP, except it adds the ability to increase the pressure provided on inspiration, which is conveniently called the inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP). Just like with CPAP, a level of continuous pressure is set, but instead of calling it CPAP, it is called the expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP). Only the name changes.

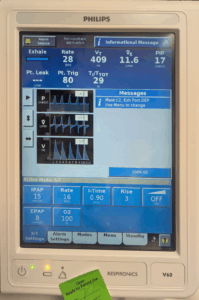

Figure 1. This patient had just been placed on bi-level positive airway pressure for mixed hypercapnic and hypoxemic respiratory failure with an inspiratory pressure of 15 cmH2O, an expiratory pressure of 8 cmH2O, and an FiO2 of 100 percent. Note that a minimum respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute was programmed, but the patient was actually breathing 28 breaths per minute. (Click to enlarge.)

With BiPAP, you now have three variables to control: the IPAP, EPAP, and FiO2, and the settings are typically read just like that: “15 over 8, 100 percent” means an IPAP of 15 cmH2O, an EPAP of 8 cmH2O, and an FiO2 of 100 percent. These are absolute values, so when the patient exhales, they get 8 cmH2O and when they inhale, they get 15 cmH2O (see Figure 1).

Adding additional pressure during inspiration generally increases the patient’s tidal volume and therefore, their minute ventilation, making it optimal for patients who have problems with ventilation, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).6,7 For these patients, the EPAP can counteract air-trapping via reduction in dynamic airway collapse, whereas the IPAP can help mitigate respiratory muscle fatigue.

Once the patient is on CPAP or BiPAP, you can adjust the settings based on the patient’s response to treatment. If they are still hypoxemic, increase the PEEP/EPAP or FiO2; if they are still hypercapnic, increase the IPAP.

Advanced NIPPV

Most noninvasive ventilation devices found in the acute care setting also allow you to apply a set (minimum) respiratory rate, in addition to the IPAP, EPAP/CPAP and FiO2, which is great for patients with an impaired respiratory drive. Conceptually, this is similar to pressure control ventilation, but that is beyond the scope of this article.

Where I have found it to be most helpful, however, is in preparing for intubation. If you are using NIPPV to preoxygenate your patients for intubation (and you probably should be, given the results of the PREOXI trial), setting a minimum respiratory rate allows you to keep the mask on the patient while giving your paralytic, providing ventilation throughout the period where they would otherwise be apneic.8

One advanced mode of NIPPV that is worth a mention is average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS). Just like in BiPAP, you will set the EPAP, FiO2, and respiratory rate. However, instead of providing a fixed inspiratory pressure, AVAPS targets a set tidal volume (and therefore a target minute ventilation) and varies the inspiratory support necessary to achieve the set target volume. So, for a typical target tidal volume of 8 mL/kg, you can set the allowable range (minimum and maximum) of inspiratory pressure and the machine will dynamically vary the pressure to assure the tidal volume that you are targeting.

AVAPS is contraindicated in the air-hungry patient, since the machine will drop the inspiratory support in response to their large tidal volumes, eliminating the support you intended, potentially making things worse. However, it is perfect for the drowsy patients with COPD, since it will increase the inspiratory pressure (and thus tidal volume) if they fall asleep, making it an auto-titrating mode of NIPPV.9 Some patients with severe obesity hypoventilation syndrome or neuromuscular weakness may have AVAPS as a nocturnal ventilation regimen.10

Using the Ventilator to Deliver NIPPV

Almost all modern ventilators have modes of support that replicate CPAP and BiPAP, typically called pressure support ventilation (PSV). When PSV is selected as the mode of ventilation (regardless of whether they are intubated or still on a non-invasive mask), the terminology changes: instead of using the term CPAP or EPAP, we use the term PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure). Yes, I know that it’s confusing that CPAP, EPAP, and PEEP are all different names for the same thing.

Figure 2. This portable ventilator is programmed to use pressure support ventilation on a non-intubated patient (NIV = non-invasive ventilation) with a positive end-expiratory pressure (CPAP) of 5 cmH2O and a pressure support of 15 cmH2O (helpfully labeled here with Pinsp to indicate that it is 15 cmH2O above the positive end-expiratory pressure when the patient inspires). The backup rate is set at 12 breaths per minute and the FiO2 is 100 percent. (Click to enlarge.)

The nomenclature surrounding the inspiratory pressure is also different. The ventilator uses the terminology of pressure support, which is defined as the level of support relative to the PEEP (instead of the IPAP, which is an absolute number). Therefore, although a patient on BiPAP might be on an IPAP of 20 and an EPAP of 5 (“20 over 5”), this would translate to a pressure support of 15 and a PEEP of 5 (“15 over 5;” see Figure 2).

Although pressure support ventilation (PSV) is great for weaning ventilator support in the ICU, the major advantage for use in the ED is for simplicity.11 If you have a patient on PPV who is progressing towards intubation, a skilled respiratory therapist can transition the patient with their noninvasive mask from the NIPPV device to the ventilator even before intubation (ventilator-assisted preoxygenation), freeing up valuable space at the bedside and allowing for an easy transition to the ventilator after placement of the endotracheal tube.12,13

Dr. Jansson is the medical director of the emergency critical care center (EC3), director of operations for the division of critical care, and an assistant professor of emergency medicine and internal medicine at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Jansson is the medical director of the emergency critical care center (EC3), director of operations for the division of critical care, and an assistant professor of emergency medicine and internal medicine at the University of Michigan.

References

- Allison MG, Winters ME. Noninvasive ventilation for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34(1):51-62.

- Kallet RH, Diaz J V. The physiologic effects of noninvasive ventilation. Respir Care. 2009;54(1):102–15.

- Seupaul RA. Evidence-based emergency medicine/systematic review abstract. Should I consider treating patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema with noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation? Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):299–300.

- Berbenetz N, Wang Y, Brown J, et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4(4):CD005351.

- Gray A, Goodacre S, Newby DE, et al. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(2):142-151.

- Rowe BH. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;43(1):133-135.

- Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, et al. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD004104.

- Gibbs KW, Semler MW, Driver BE, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for preoxygenation during emergency intubation. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(23):2165-2177.

- Briones Claudett KH, Briones Claudett M, Chung Sang Wong M, et al. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation with average volume assured pressure support (AVAPS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypercapnic encephalopathy. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13(1):12.

- Storre JH, Seuthe B, Fiechter R, et al. Average volume-assured pressure support in obesity hypoventilation: a randomized crossover trial. Chest. 2006;130(3):815-821.

- Ladeira MT, Vital FMR, Andriolo RB, et al. Pressure support versus T-tube for weaning from mechanical ventilation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(5):CD006056.

- Latona A, Pellatt R, Wedgwood D, et al. Ventilator-assisted preoxygenation in an aeromedical retrieval setting. Emerg Med Australas. 2024;36(4):596-603.

- Grant S, Khan F, Keijzers G, et al. Ventilator-assisted preoxygenation: protocol for combining non-invasive ventilation and apnoeic oxygenation using a portable ventilator. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(1):67-72.

No Responses to “Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Emergency Department”