Looking back on my residency days, I have fond memories of calling for positive pressure ventilation (PPV) for a patient in respiratory distress, and confidently responding “10 over 5” when the respiratory therapist asked what settings I wanted. It was only after completing critical care fellowship that I realized that the respiratory therapist had actually been nodding knowingly at me, then proceeding to adjust the settings to what the patient actually needed. In this month’s column, I will aim to demystify the alphabet soup of PPV and add some tips and tricks from the intensive care unit.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: October 2025 (Digital)CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most basic mode of noninvasive PPV (NIPPV). CPAP involves the continuous application of a set level of positive pressure throughout the respiratory cycle, regardless of whether the patient is inhaling, exhaling, or even apneic. With CPAP, you generally have two variables to control: the level of CPAP (given in centimeters of water, or cmH2O), and the oxygen concentration (given as fraction of inspired oxygen, or FiO2) .1

CPAP is generally best for patients with oxygenation problems. Increasing the FiO2 raises the percentage of oxygen delivered, whereas increasing the level of CPAP raises the mean airway pressure and recruits more lung tissue to participate in gas exchange. Physiologically, as the level of CPAP is increased, intrathoracic pressure increases, causing a decrease in both preload and afterload, and an increase in recruited lung tissue, particularly for areas of atelectasis or pulmonary edema.2 Because of this physiology, it should be your first choice for patients with acute pulmonary edema.3-5

BiPAP

Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) is conceptually similar to CPAP, except it adds the ability to increase the pressure provided on inspiration, which is conveniently called the inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP). Just like with CPAP, a level of continuous pressure is set, but instead of calling it CPAP, it is called the expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP). Only the name changes.

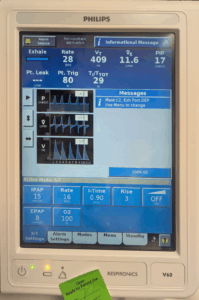

Figure 1. This patient had just been placed on bi-level positive airway pressure for mixed hypercapnic and hypoxemic respiratory failure with an inspiratory pressure of 15 cmH2O, an expiratory pressure of 8 cmH2O, and an FiO2 of 100 percent. Note that a minimum respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute was programmed, but the patient was actually breathing 28 breaths per minute. (Click to enlarge.)

With BiPAP, you now have three variables to control: the IPAP, EPAP, and FiO2, and the settings are typically read just like that: “15 over 8, 100 percent” means an IPAP of 15 cmH2O, an EPAP of 8 cmH2O, and an FiO2 of 100 percent. These are absolute values, so when the patient exhales, they get 8 cmH2O and when they inhale, they get 15 cmH2O (see Figure 1).

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

No Responses to “Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Emergency Department”