An emergency physician gets ready for work, secures two ballpoint pens, a permanent marker, and a penlight in her pocket, taking her first sip of coffee before logging in for a single coverage morning. A chief medical officer (CMO) gets ready for work, adjusts his tie and sleeves, and pulls into the hospital parking lot. A gentleman gets ready for work — combs his salt and pepper hair back, taking one last draw from the cigarette — then watches the smoke blend into the sunrise haze.

Explore This Issue

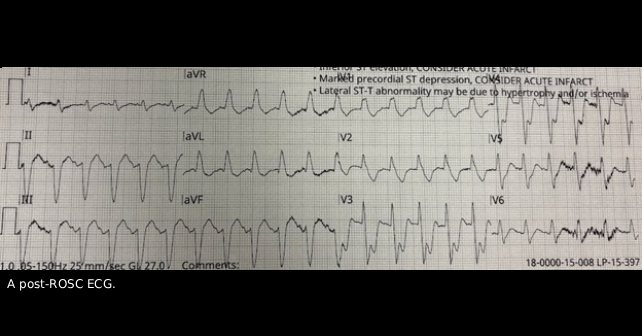

ACEP Now: November 2025My patient’s wife Jean tells me she and Mark have been married for longer than 30 years and every morning before work, Mark smoked a cigarette on the front porch. After that morning’s cigarette, Mark had a coughing fit and collapsed in their hallway. Jean started CPR and EMS delivered a shock for ventricular fibrillation with administration of epinephrine with amiodarone and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) obtained with a post-ROSC ECG sent over (see figure above). During transport, Mark lost pulses again. Upon entrance to the emergency department (ED), we gave intravenous tenecteplase, rectal aspirin, and epinephrine. Unfortunately, his ejection fraction on point-of-care ultrasound was severely depressed with a regional wall motion abnormality, requiring escalating epinephrine and dobutamine to maintain a perfusing blood pressure by arterial monitoring. For more than an hour and a half, he lost pulses three more times; countless other patients waited to be seen.

The CMO rolled up his sleeves, loosened his tie, and came to the ED to coordinate consultation/transfer, input orders, and helped with tucking in other patients. This was not surprising for our CMO. Daily, he walks through the hospital floors and ED, a physician leader who lives his values as someone with dependable humility.

Our individual values are principles we live by, a source of meaning, and the “why” behind our actions. Values can be interpreted as “common sense.” However, can you truly describe your values to your partner or a friend? Could you define them as an organization does as, for example, the U.S. Army’s seven core values? Values can also be interpreted as “fluff” or impractical. However, defining our values improves our wellbeing as physicians.

West and colleagues performed a randomized, controlled trial of 74 physicians at the Mayo Clinic. In the intervention group, physicians attended biweekly modules, which included small group sessions with reflection on their values. Compared with controls, work engagement increased and depersonalization scales, perceived stress scales, and overall burnout rates decreased at 3- and 12-month follow-up in the intervention group.1 Furthermore, defining our values can guide us in those difficult decisions. Coming back to our values in these times can help us make the decisions that we are content with at the end of the day.

We’ll discuss a blueprint on narrowing down what values are important to us through the process: Discovery → Identify → Expression → Behavior.

Establish Core Values

Start by scanning the values list in our word cloud. All are admirable values, but not all can be core values.2-4 Core values are meant to be unique to you, present even when no one is watching. They’re not our organization’s values or even the values of our closest confidants. They are not the expected values of “being a physician” in the eyes of the public, our mentors, parents, friends, or partners. They are our individual beliefs of what it means to be fulfilled, to have a shift well-played, and be the best physician we strive to be.

Terms may seem synonymous but resonate differently with different people. For example, reliability and dependability overlap definitions, but someone may interpret reliability as more task-based (i.e., consistently showing up to shift early or finishing notes on time) and dependability as more emotion-based (i.e., keep the confidence of colleagues in times of crisis).

To unearth your core values, systematically reflect on three key areas: impactful moments, role models, and your desired legacy.

What makes an impactful moment? “Peak” moments encompass experiences in which you feel a sense of flow, ikigai, and meaning. “Violating” moments are those that make you feel visceral defensiveness. Analyze those moments carefully. What is it about that peak moment for the end-of-life care that you rendered? Did you find deep meaning in the competence or leadership of running the code expertly? Did you find flow in the openness of speaking honestly and compassionately with family members?

Conversely, what was it about the sign out from a well-intentioned colleague that deeply troubled you when reevaluating the patient? Was it most jarring that there may be a lack of understanding when the patient was instructed to keep his diabetic ulcers clean but had no ready access to running water, shoes, or dressing supplies? Hidden in those moments are your core values, either expressed or breached.

Consider those you admire. What behaviors do they display? Is it respect manifested as your colleague who always sits or kneels when talking to a patient, bed, or hallway? Is it adaptability when you see your charge nurse flexing to triage a patient and teaching continuous bladder irrigation to a new nurse while running the flow of incoming ambulances?

Lastly, imagine that last shift of your career. When you walk out of the ambulance bay for the final time, what is it that people felt working with you? Perhaps they remember how you treasured community, coordinating ED fishbowl baby showers or buying Tuesday pizza and paging overhead, “Attention, stat gastric resuscitation in break room.” Or perhaps they remember you for unwavering duty — during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, you stayed hours after your shift in powered air-purifying respirators to cover for a COVID-afflicted colleague.

Select or create those three to five core values that speak to you from reflection.

Evoke a “Totem”

Create a tangible representation — or “totem” — that embodies your core values. You could define it further, as if from a dictionary. For example, a totem for candor can be defined by, “I speak my truth clearly and directly, with respect and integrity.” Another totem may be a personal statement or essay as suggested by Burnett and Evans or Covey. Others may find their totem in creative outlets as an artistic piece, imagery, lines of poetry, mantras, or musical lyrics that capture the essence of their core values.5 Some of us may already do this in part without knowing it. Clothing choices, as is shoe choice on shift, may be a totem of your underlying values — running shoes, clogs, or riding boots.

The totem is a grounding element. It is not just a starting point for executing behaviors, but also an endpoint to come to when situations become difficult. Thus, deliberately creating a totem that is memorable and simple for you allows easy accessibility. When we are faced with particularly challenging situations, evoking this totem can remind us of what is important to us.

Execute with Intention

Sustain and develop behaviors that align with those values. In Dare to Lead, Brown describes “operationalizing” values into discrete behaviors for which we are held accountable.2 For example, behavioral execution of the inclusion for an ED or educational leader could manifest as:

- Providing space for follow-up and input after a meeting,

- Calling out those that are interrupting others, and

- Asking specific people for their valuable input that may not be shared otherwise.

- Leveraging heuristics to engrain value-based behaviors can be empowering. Building heuristics as, “For every patient with an upper extremity injury, I ask about hand dominance and occupation,” or “Every patient with falls, I ask about their living situation and mobility,” or “For every parent, I ask if they need a school/daycare note,” may “automate” an underlying value of understanding. An interval feedback mechanism could be internal or external, such as checking in with oneself or a trusted peer on a weekly basis to see if those value-driven behaviors are executed.

In Atomic Habits, Clear describes fostering an environment (“Make it Easy”) conducive for desired behaviors.4 That environment can be as concrete as your ED workstation to the patients or colleagues. Perhaps you have your Dragon PowerMic Command of “Open Websites” to auto-open UpToDate or OpenEvidence to foster curiosity when a clinical question comes up. Or you create a gratitude form or template for deserving colleagues that takes only a minute and a few clicks to fill out. Or you simply schedule monthly coffee or walks with a peer whose values align with yours. Make the environment work for your values.

Making others aware of your values can be sharing your values, totems, and behaviors with them. However, a more natural and indirect way is in the feedback we give others. By pointing out behaviors that we agree or disagree with, we are mirroring our values for those we give feedback to. “Thank you for going the extra mile and filling out the discharge paperwork for your sign out” may mirror your values of thoroughness or consideration.

Closing Thoughts

Values shouldn’t be confused as the sole guiding principle for all our behaviors and interactions. As a compass, values give us direction, but no further information as to the best route. To rely solely on values is to warp it into vices. An overcommitment to dependability without boundaries or loyalty without insight is burnout or naive allegiance, respectively. As is in almost everything in medicine, values are a balance and taken into context of the circumstances and our practice environments. Also, it’s important to remember that values are different amongst us all. Being cognizant of this can help us foster understanding between colleagues and improve feedback. Our values may not align with others’ values, thus we should be mindful of judging based on differing values.

At the end of the day, our values are what carries on within us, whether on shift, across a career, or in our lives. To define them is to respect and invest in ourselves. In difficult times, decisions, or shifts, values can be a guiding light to make the right call because at the end of the shift, we want to reflect and feel that we lived our values.

Jean cried softly in a quiet resuscitation. I saw Mark’s arterial waveform spike with each compression from the LUCAS, hold with each push of epi, then slowly dwindle each rhythm and pulse check. His heart tapped faintly on echo. Jean held his hand — first warm, then pale, then mottling hand. She smoothed his salt and pepper hair. Trying to offer comfort, I said, “Some believe hearing is the last sense to leave.” I wasn’t sure I fully believed it — but in that moment, I did. Jean stroked his hair again and whispered, “You lived such a good life. A great life.”

Dr. Koo is a faculty member and an emergency physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, D.C., and St. Mary’s Hospital in Leonardtown, Md.

Dr. Koo is a faculty member and an emergency physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, D.C., and St. Mary’s Hospital in Leonardtown, Md.

References

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

- Brown, Brené. Dare to Lead. New York, Random House, 2018.

- Burnett, Bill and Evans, David. Designing Your Life: Build a Life That Works for You. London, Vintage Books, 2018.

- Clear, James. Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones. Go BOOKS, 2019.

- Bayer, Mike. Best Self: Be You, Only Better. Dey Street Books, 2019.

- Covey, Stephen R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York, Simon & Schuster Ltd, 1989.

No Responses to “Let Core Values Help Guide Patient Care”