An emergency physician gets ready for work, secures two ballpoint pens, a permanent marker, and a penlight in her pocket, taking her first sip of coffee before logging in for a single coverage morning. A chief medical officer (CMO) gets ready for work, adjusts his tie and sleeves, and pulls into the hospital parking lot. A gentleman gets ready for work — combs his salt and pepper hair back, taking one last draw from the cigarette — then watches the smoke blend into the sunrise haze.

Explore This Issue

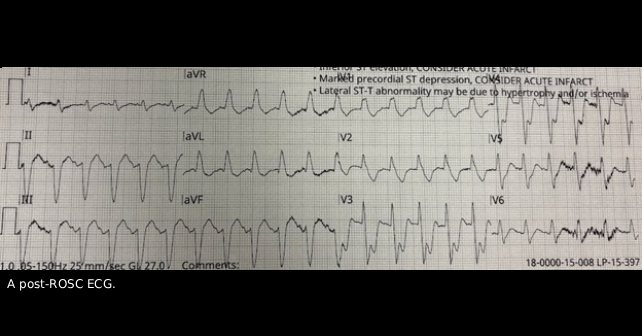

ACEP Now: November 2025My patient’s wife Jean tells me she and Mark have been married for longer than 30 years and every morning before work, Mark smoked a cigarette on the front porch. After that morning’s cigarette, Mark had a coughing fit and collapsed in their hallway. Jean started CPR and EMS delivered a shock for ventricular fibrillation with administration of epinephrine with amiodarone and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) obtained with a post-ROSC ECG sent over (see figure above). During transport, Mark lost pulses again. Upon entrance to the emergency department (ED), we gave intravenous tenecteplase, rectal aspirin, and epinephrine. Unfortunately, his ejection fraction on point-of-care ultrasound was severely depressed with a regional wall motion abnormality, requiring escalating epinephrine and dobutamine to maintain a perfusing blood pressure by arterial monitoring. For more than an hour and a half, he lost pulses three more times; countless other patients waited to be seen.

The CMO rolled up his sleeves, loosened his tie, and came to the ED to coordinate consultation/transfer, input orders, and helped with tucking in other patients. This was not surprising for our CMO. Daily, he walks through the hospital floors and ED, a physician leader who lives his values as someone with dependable humility.

Our individual values are principles we live by, a source of meaning, and the “why” behind our actions. Values can be interpreted as “common sense.” However, can you truly describe your values to your partner or a friend? Could you define them as an organization does as, for example, the U.S. Army’s seven core values? Values can also be interpreted as “fluff” or impractical. However, defining our values improves our wellbeing as physicians.

West and colleagues performed a randomized, controlled trial of 74 physicians at the Mayo Clinic. In the intervention group, physicians attended biweekly modules, which included small group sessions with reflection on their values. Compared with controls, work engagement increased and depersonalization scales, perceived stress scales, and overall burnout rates decreased at 3- and 12-month follow-up in the intervention group.1 Furthermore, defining our values can guide us in those difficult decisions. Coming back to our values in these times can help us make the decisions that we are content with at the end of the day.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

No Responses to “Let Core Values Help Guide Patient Care”