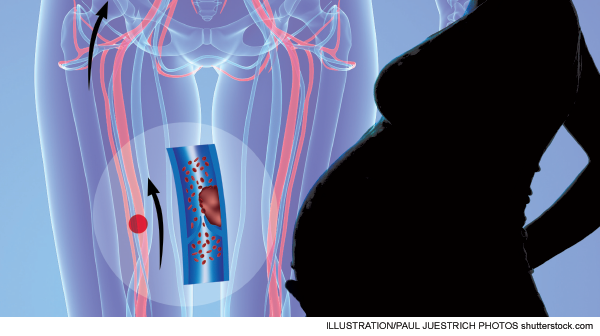

Common assessment methods including clinical decision rules, D-dimers, and PERC rules have limited use in detecting VTE in pregnancy

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014With so much debate and controversy regarding the evaluation of venothromboembolic disease (VTE) and with much of the debate centering on methods of risk stratification to avoid the expense and risks associated with overtesting, it is very easy to overlook patients who just don’t belong in this discussion.

You like clinical decision rules (CDRs)? Great! You can cast your vote for which ones you like, when to apply them, to whom they should apply, what pre-test probabilities are acceptable for assigning low risk, and, of course, which have been adequately validated.

You’re a D-dimer fan? Fine! (For now.) Which D-dimer are you using, is your D-dimer “highly sensitive,” what is the post-test probability for a negative test, and what should you do with positive results?

There are many good questions and many good debates, which will eventually lead to even better answers.

Surprisingly, VTE in pregnancy has been conspicuously absent from the data that are guiding these discussions, and that absence of data, from my perspective, makes decision-making in this at-risk population pretty easy. In short, if you have clinical suspicion, you should probably just study ’em all. Heresy! Just irradiate all of those expectant mothers?! No, not exactly. In an attempt to do the right thing, physicians may feel that the lack of evidence in this population seems to point to evaluation in favor of cost reduction, reduced radiation exposure, etc. The lesser of two evils is diagnostic evaluation when the alternative is missed or delayed diagnoses. Remember, the short answer on risk stratification is that these patients are not low-risk patients and should not be classified as such.

Let’s examine four essential areas of the VTE debate, but in the specific context of pregnancy: risk, CDRs, D-dimers, and ultrasound evaluation.

The data are clear; VTE is pregnancy is more common than many think. Marik and Plante published an excellent review in 2008 that highlighted some important statistics about VTE in pregnancy.1 The incidence of VTE in pregnancy is estimated to be 0.76–1.72 per 1,000 pregnancies, indicating four times the risk compared to nonpregnant patients. Two-thirds of DVTs occur prior to delivery (antepartum) and are equally distributed among all three trimesters, and 43–60 percent of pregnancy-related pulmonary emobli (PE) occur in puerperium (roughly the six-week time period extending from delivery). Greer reported similar findings in his review: “The relative risk of antenatal VTE is approximately fivefold higher in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women of the same age.”2 He also reported the absolute risk to be 1 in 1,000 pregnancies. Most interesting is that 50 percent of VTE cases occur in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (early pregnancy); many clinicians are under the misconception that this is a relatively low-risk gestational period. Puerperium was similarly reported as the period with the highest risk, with a relative risk of 20-fold. This article also provides some insight as to risk factors: previous VTE (odds ratio 24.8), immobilization (7.7), BMI >30 (5.3), BMI >25 combined with immobilization (62), smoking (2.7), preeclampsia (3.1), and C-section (3.6).

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Lack of Data for Evaluating Venothromboembolic Disease In Pregnant Patients Leaves Physicians Looking for Best Approach”