Case: A 54-year-old male presents to your emergency department the day after being involved in a snowmobile accident on the weekend. He reports he was riding his sled along an embankment when it rolled. He thought it would get better, but the chest pain and shortness of breath have gotten worse over the past 48 hours. His vital signs are normal, and the physical exam indicates he has bruising and tenderness over the left chest wall, with diminished left-sided lung sounds. A CT scan reveals three rib fractures and a hemothorax estimated to measure 600 cc, with no additional injuries.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 03 – March 2022Clinical Question: Are small pigtail catheters (PCs) as effective as large-bore chest tubes (LBCTs) for the treatment of hemodynamically stable patients with traumatic hemothorax?

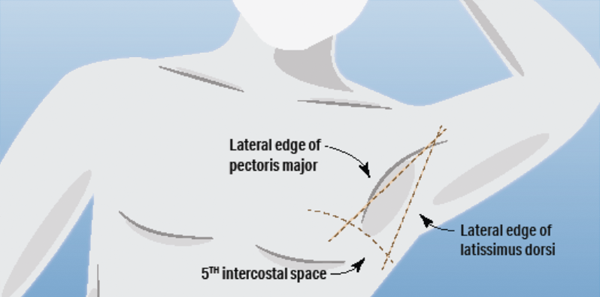

Background: Traumatic hemothoraces have been traditionally treated with LBCTs. It is important to place these in the pleural space and in the zone of safety. Whether the tube is directed up or down does not seem to be associated with outcomes.1

A small observational study looked at 36 patients with traumatic hemothorax or hemopneumothorax receiving a PC and compared them to 191 patients receiving a LBCT. The small catheter seemed to work just as well as the LBCT.2

Reference: Kulvatunyou N, Bauman ZM, Edine SBZ, et al. The small (14 Fr) percutaneous catheter (P-CAT) versus large (28–32 Fr) open chest tube for traumatic hemothorax: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Trauma and Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(5):809-813.

- Population: Hemodynamically stable adult patients 18 years or older suffering traumatic hemothorax or hemopneumothorax requiring drainage at the discretion of the treating physician

- Exclusions: Emergent indication, hemodynamic instability, patient refuses to participate, prisoner or pregnancy

- Intervention: Small (14 Fr) pigtail catheter

- Comparison: Large (28–32 Fr) large-bore chest tube

- Outcome:

- Primary Outcome: Failure rate defined as radiographically apparent hemothorax after tube placement requiring an additional intervention, such as second tube placement, thrombolysis or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

- Secondary Outcomes: Insertion complication rate; drainage output (30 minutes, 24-hour, 48-hour and 72-hour); hospital course outcome up to 30 days (total tube days, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay and ventilator days); and insertion perception experience (IPE) score (1–5 subjective score, with 1 meaning “it was okay” to 5 meaning “it was the worst experience of my life”)

- Trial Design: Multicenter, noninferior, unblinded, randomized, parallel assignment comparison trial

Authors’ Conclusions: “Small caliber 14-Fr PCs are equally as effective as 28- to 32-Fr chest tubes in their ability to drain traumatic HTX with no difference in complications. Patients reported better IPE scores with PCs over chest tubes, suggesting that PCs are better tolerated.”

Results: They identified 222 eligible patients over five years, with 119 (56 PC and 63 LBCT) included in the final cohort. The mean age was 55 years, 82 percent were male, 81 percent had blunt trauma and median time to tube placement was one to two days after injury.

Key Result: Pigtail catheters were noninferior to large-bore chest tubes for treating traumatic hemothorax and hemopneumothorax.

- Primary Outcome: Failure rate was 11 percent for PC versus 13 percent for LBCT (P=0.74).

- Secondary Outcomes: There were two insertion-related complications, one from each group (bleeding from PC necessitated a thoracotomy, and extra pleural position from chest tube placement required another tube placement). There were two deaths, one from each group (PC group had a PE on postinjury day 10 and the tube had already been removed, and LBCT group had a nontrauma-related death at an outside institution). There was no statistical difference between PC and LBCT in terms of drainage tube output except at 30 minutes, with more in the PC group. There was no statistical difference in hospital course. Patients reported better IPE scores in the PC group compared to the LBCT group.

EBM Commentary:

- Selection Bias: There were 102 patients excluded from the 222 eligible. Twenty-seven of the exclusions were for “MD preference.” This could have introduced some selection bias into the trial.

- Unstable Patients: Hemodynamically unstable trauma patients were also excluded from this trial. Open thoracostomy and the placement of a LBCT is still considered by many to be the primary treatment for the evacuation of hemothorax in the hemodynamically unstable trauma patient. The exclusion of hemodynamically unstable patients could also explain the lower-than-anticipated failure rate, which is discussed below. Further research will be needed to determine if PC catheters are noninferior to LBCTs in hemodynamically unstable trauma patients.

- Patient-Oriented Outcome: Tube failure rate seems like a disease-oriented outcome (DOO). The IPE score seems like a more patient-oriented outcome (POO). Patients did prefer the PC compared to the LBCT. However, the IPE scale developed by the investigators has not been externally validated.

- Low Overall Failure Rates: The failure rates in this study were 11 percent and 13 percent for PCs and LBCTs, respectively. These figures are significantly lower than the rate of 28.7 percent reported in a recent multi-institutional study from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). This may be because the study excluded patients in extremis, as the authors point out in the discussion. However, the study population in this trial had a mean hemothorax volume of 612 mL versus 191 mL is the EAST study. This indicates that volume of blood did not appear to influence rate of failure compared to what has been published elsewhere.3

- Stopped Early: This trial was stopped before reaching its goal of 190 patients, despite enrolling at four sites for five years. The authors reported slow enrollment and disruption to research caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. They did conduct an interim analysis prior to stopping enrollment, and their primary endpoint still met the prespecified noninferior margin.

SGEM Bottom Line: Offering a pigtail catheter instead of a large-bore chest tube for the evacuation of a traumatic hemothorax in a hemodynamically stable patient is reasonable.

Case Resolution: The patient is offered the traditional LBCT or the pigtail. He decides to go with the small catheter, which is placed without any complications. He is admitted to the trauma service for pain management and monitoring. The PC is removed on day three of hospitalization, and he is discharged on day five.

Thank you to Dr. Chris Root, a second-year resident physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for his help with this review.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you heard it on the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

References

- Benns MV, Egger ME, Harbrecht BG, et al. Does chest tube location matter? An analysis of chest tube position and the need for secondary interventions. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(2):386-390.

- Kulvatunyou N, Joseph B, Friese RS, et al. 14 French pigtail catheters placed by surgeons to drain blood on trauma patients: is 14-Fr too small? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1423-1427.

- Prakash PS, Moore SA, Rezende-Neto JB, et al. Predictors of retained hemothorax in trauma: results of an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma multi-institutional trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(4):679-685.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “How Do Small and Large Catheters Compare in Hemodynamically Stable Patients?”