Part 2 of a 3-part series. Part 1. Part 3.

Explore This Issue

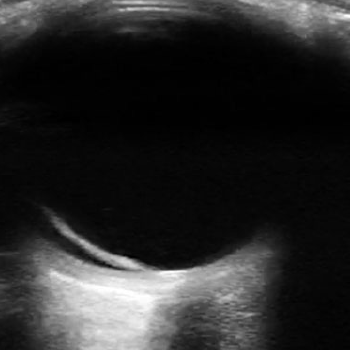

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 04 – April 2019Figure 1: The optic nerve appears posteriorly as a hypoechoic structure and is measured 3 mm posterior to the globe.

The Case

Monday, 23:00—You notice a worried mother pacing back and forth in front of another room. You speak with her and find that she is concerned about her daughter who is here with headaches and blurry vision. You find an obese 17-year-old female anxiously sitting on the ED stretcher. She says she can “deal” with the headaches she’s been having, but now that her vision is blurry, she is extremely upset and didn’t want to wait until morning to call her pediatrician. You anticipate a CT scan won’t provide much information and wonder what more you can do rapidly to assess her.

Common Emergency Department Application

Structure: Optic Nerve

Evaluate for: Elevated Intracranial Pressure

Measurement of the optic nerve sheath diameter is a quick, simple, and noninvasive method to evaluate for elevated intracranial pressure (EICP). The optic nerve is encased in a sheath that is then contiguous with the dura mater and through which cerebrospinal fluid slowly permeates. Although changes in the optic nerve sheath may lag behind acute EICP, its measurement can still add valuable diagnostic information. The direct correlation between the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) and intracranial pressure has been well-established, but what measurements can rule in or rule out EICP?

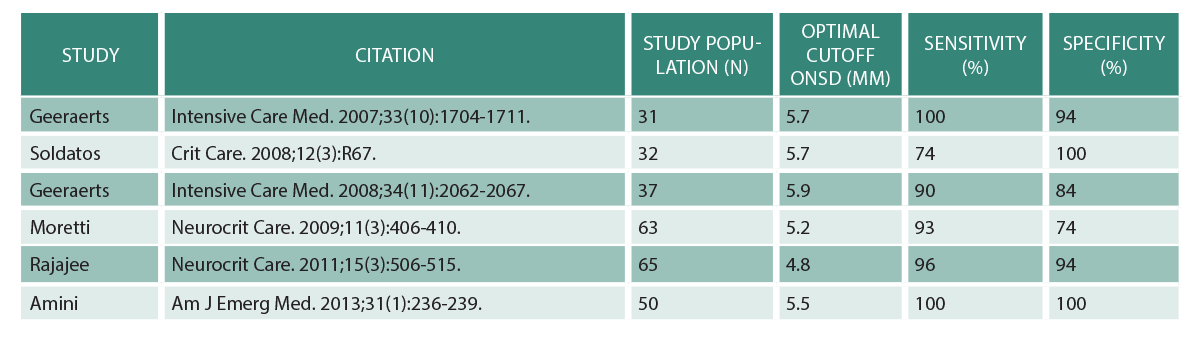

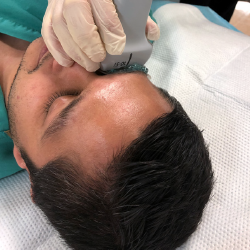

The optic nerve appears posteriorly as a hypoechoic structure and is measured 3 mm posterior to the globe (see Figure 1). Measure the ONSD bilaterally and average the two values. Generally, ≤5 mm is considered normal in an adult (>18 years), and ≤4.5 mm is considered normal in a child (1–17 years). Several studies have investigated patients’ ONSD compared with the presence or absence of increased intracranial pressure in an attempt to establish the best cutoff value. Table 1 summarizes the optimal ONSD cutoffs and their corresponding sensitivities and specificities for EICP from a selection of the literature. The values range from 4.8 mm to 6.0 mm, although a higher cutoff value did not necessarily mean greater sensitivity and specificity.1 A systematic review and meta-analysis found that an ONSD cutoff of 5 mm demonstrated high sensitivities and specificities when compared with traditional CT scan for detecting EICP.2

(click for larger image) Table 1: Optimal Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter Cutoffs

Adapted from Parker C. Optic nerve sheath diameter: window to the soul? BroomeDocs.com Clinical Blog. 2014.

Case Resolutions

So what happened with the patient? After offering reassurance to her mother, you discuss with her the utility of POCUS for her daughter’s complaints. With ultrasound, you rapidly identify the patient’s optic nerve and recognize enlargement bilaterally. Given your concern for increased intracranial pressure, an MRI and lumbar puncture are performed, confirming the diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The patient and mother are extremely grateful and impressed by your handy bedside ultrasound skills in detecting what was causing her visual disturbance.

Ocular ultrasound is easy to learn and can rapidly assess ocular emergencies. With practice, you can easily incorporate POCUS into your diagnostic algorithm and rule in or out important ocular pathology.

References

- Parker C. Optic nerve sheath diameter: window to the soul? Broome Docs website. Accessed Feb. 15, 2019.

- Ohle R, McIsaac SM, Woo MY, et al. Sonography of the optic nerve sheath diameter for detection of raised intracranial pressure compared to computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1285-1294.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “High-Yield Ocular Ultrasound Applications in the ED, Part 2”