Part 1 of a 3-part series. Part 2. Part 3.

The Case

Monday, 23:00—Your first patient of the night is a 65-year-old male with “no medical problems” who reports loss of vision in his right eye for the past two days. He thought it might just “go away,” but now that it hasn’t, he has placed his vision in your hands. A quick visual acuity test reveals 20/200 in the affected eye, and your attempt at a funduscopic exam reveals what you would describe as a blur of yellow and red. You have a sense of what is going on with this patient. However, you want more objective information before you speak with the ophthalmologist.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 03 – March 2019Discussion

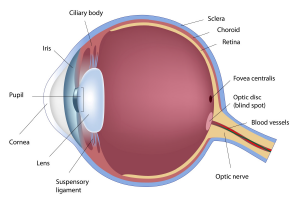

The use of ocular ultrasonography for the evaluation of emergency patients has been well-established in the emergency medicine literature. The anatomy of the eye is very complex, but luckily, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can identify the key structures. The eye is a fluid-filled structure, which makes for an easy organ to visualize. With practice, POCUS can easily be incorporated into the workup of patients with ocular complaints to avoid lengthy consultation or other diagnostic tests.

The first application of diagnostic ocular ultrasound was reported by Mundt and Hughes in 1956 when diagnosing an eye tumor. Prior to ultrasound, in vivo ocular lengths and other measurements proved difficult to obtain. However, all the measurements of an eye can now be obtained by a handheld transducer.1 Today, POCUS is beyond savvy and can essentially replace the dilated funduscopic eye exam for emergency physicians. We will review the normal eye anatomy on ultrasound, techniques for the exam, as well as some high-yield ED applications on our tour of the globe!

Common Emergency Department Application

Structure: Retina

Evaluate for: Retinal Detachment

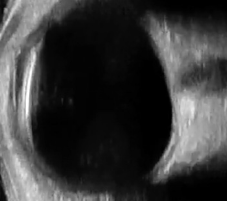

The retina is a crucial structure to evaluate for patients with visual complaints. In a normal eye, the retina cannot be distinguished from the other posterior layers, appearing as one homogenous structure.2 The retina is anchored at the ora serrata laterally and the optic nerve posteriorly. This will be important later on when distinguishing retinal versus vitreous detachments.

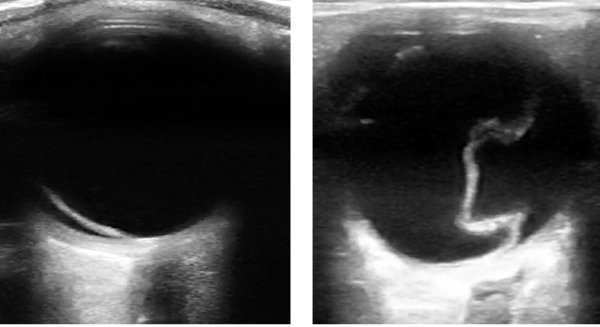

Figure 6 (LEFT): In retinal detachment, the retinal membrane will be lifted off of the posterior or lateral globe and appear as a hyperechoic (bright white) and sometimes serpiginous membrane.

Figure 7 (RIGHT): A detached retina may take on a funnel-shaped appearance.

A normal retina should be closely attached to the posterior wall of the globe such that on ultrasound there will be no distinction between the two. In the case of retinal detachment, the retinal membrane will be lifted off the posterior or lateral globe and appear as a hyperechoic (bright white) and sometimes serpiginous membrane (see Figure 6). Because of its firm attachment to the optic disc, a detached retina may take on a funnel-shaped appearance, and you will see it tethered to the optic nerve (see Figure 7). The retina’s attachment to the optic nerve posteriorly will be preserved even in the case of a retinal detachment, which is an important detail when distinguishing it from other detachments. With patient eye movements, the membrane may undulate or wave.

Involvement of the macula, in the case of retinal detachment, is a critical piece of information to obtain. The macula contains structures specialized for high-acuity vision and is located perpendicular to the lens. Once you have obtained a clear image of the retinal detachment with the lens included in the image, draw a straight line connecting the middle of the lens to the posterior wall of the globe. The area you encounter is the macula, and if it is still attached, your consult to ophthalmology becomes emergent rather than urgent. Preventing further detachment of the macula is paramount and could be a vision-saving act.

POCUS for retinal detachment has been shown to not only be possible but also accurate and precise among emergency physicians. According to a systematic review of the literature, sensitivities range from 97 to 100 percent, and specificities range from 83 to 100 percent. In a study by Blaivas et al, all retinal detachments diagnosed by ocular ultrasound performed by emergency physicians were later confirmed by a formal, masked ophthalmology evaluation, demonstrating its high specificity.3,4,5

Tips and Tricks: Be sure to scan through the entire retina and encourage eye movement while scanning as there may be small detachments of the peripheral retina that are easily overlooked.

Case Resolution

So what about the 65-year-old man with acute vision loss? After performing your funduscopic exam, you bring the ultrasound bedside and scan your patient’s eye. You immediately notice a retinal detachment and call the ophthalmologist, who is able to see the patient immediately in her office. On the way out, your patient thanks you for your quick diagnostic skills.

Ocular ultrasound is easy to learn and can rapidly assess ocular emergencies. With practice, you can easily incorporate POCUS into your diagnostic algorithm and rule in or out important ocular pathology.

Part 2 will appear in the April issue.

References

- Lizzi F, Coleman DJ. History of ophthalmic ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23(10):1255-1266.

- Lyon M, Blaivas M. Ocular ultrasound. In: Emergency Ultrasound. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008: 449-462.

- Jacobsen B, Lahham S, Lahham S, et al. Retrospective review of ocular point-of-care ultrasound for detection of retinal detachment. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(2):196-200.

- Blaisvas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. A study of bedside ocular ultrasonography in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(8):791-799.

- Vrablik ME, Snead GR, Minnigan HJ, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of bedside ocular ultrasonography for the diagnosis of retinal detachment: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(2):199–203.e1.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “High-Yield Ocular Ultrasound Applications in the ED, Part 1”

March 25, 2019

Thomas Benzoni, DO“Contraindications to the exam include high suspicion of globe rupture.”

This is a common misunderstanding.

In fact, trauma and suspicion of ruptured globe is one of the tremendously positive indications for ultrasound.

I make here an assumption that you suspect trauma or rupture and that you know not to put pressure on the globe. But that is the great thing about U/S: more goop and stand off a bit. You’ll have 0 pressure.

Compare that to any touching the eyelid to say nothing of retracting the lid.

You’re looking for obvious rupture/non-round structure.

Let’s myth-bust and use U/S to diagnose globe rupture.