In the emergency department (ED), care for patients with substance use disorders, and in particular, those with opioid use disorder (OUD), is limited by numerous factors: inadequate clinician education, interpersonal stigma, insufficient social services support infrastructure, competing priorities, and high utilization.1-4 Intuitively, interventions aimed at improving access to care for this population benefit patients by increased retention in outpatient care, lowered frequency of harmful substance use, decreased transmission of infectious disease, and even reductions in morbidity and mortality.5-6 These interventions can also benefit ED clinicians and health systems through improved connectivity with outpatient follow-up, decreased ED return rates and hospital readmissions, and, in turn, potential cost savings.7

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: February 2026 (Digital)However, care for patients with OUD is multidisciplinary, extending outside of the ED. These patients are cared for in every department, ranging from cardiothoracic surgery to psychiatry and every care setting, from outpatient clinics to hospital wards to the ED. Access to addiction-trained subspecialists through consult services remains limited.8 Taken together, interventions focused on caring for patients with OUD can be decentralized, without a clear stakeholder leading or “owning” this important work. This raises the question: How can emergency clinicians involve themselves in interventions that aim to improve outcomes for this patient population when they extend far beyond ED walls?

An Example Case

In June 2025, an ED at a large, urban, multi-site academic health system organized and facilitated a system-wide panel of about 20 experts in the care of patients with OUD. Experts included emergency clinicians, psychiatrists, pain specialists, community-based primary care physicians, informaticists, population health specialists, and more. These experts came from multiple hospital and outpatient sites, many without existing working relationships or prior interpersonal connections. Over four hours, this expert panel outlined the care journey for patients with OUD across the health system, with attention to identifying care gaps, and subsequently brainstorming solutions.

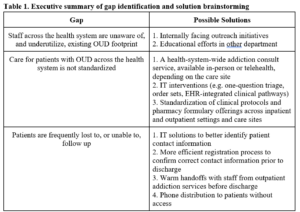

An executive summary that included a qualitative situation assessment, in addition to an organized list of gaps, potential solutions, and outstanding questions, identified poor standardization of care and frequent loss to follow up as major issues. Potential solutions ranged from easy-to-implement quick wins, such as scaling existing interventions to new care sites within the health system, to bigger picture system-level changes, with examples included in Table 1.

In the months since completion, this summary has been socialized with health system leadership. It now factors into ongoing decision making about resource allocation and intervention prioritization. In returning to their respective functions across the health system, panel experts are using this summary as a tool to inform their future areas of investigation and intervention. Specific projects initiated following this panel include: (1) creating a health system-wide, EHR-integrated clinical pathway guiding withdrawal management to standardize care across different care sites, (2) improving care coordination at transition points, including transfers to inpatient detoxification and discharge referrals to outpatient resources, (3) streamlining EHR-integrated best practice advisories and order sets to optimize treatment prescribing and referral, and (4) building a case for increased access to addiction-trained subspecialists. Additional projects addressing gaps identified through this panel are expected in the coming months.

Reflections

In facilitating this expert panel and organizing outputs, we were prompted to reflect more broadly on the role of emergency medicine, as a field, and as individual physicians, in health system-level interventions aimed at improving outcomes for patients with OUD.

First, the breadth of backgrounds and experiences among panel experts is a testament to how widely patients with OUD are spread across the health system. Despite working with and caring for this patient population, many panel members had not collaborated prior to this exercise. Without coordination, efforts risk becoming decentralized and siloed, consistent with the observation of poor standardization of care across the health system. Cross-departmental collaboration is necessary to implement meaningful, lasting interventions that impact patient populations who span care settings. Though patients with OUD are one such example, the same lesson could be applied to similar transient populations, including patients with sickle cell disease or chronic pain, or those who are incarcerated or pregnant.

No clear single stakeholder owns this work. As a result, the need for leadership—including organization and coordination of ongoing and future efforts—is evident. We propose that emergency physicians could lead it. Emergency medicine leadership for addiction care at the patient, institutional, health system, and national level is both practical and morally imperative. Interventions stemming from this expert panel will benefit emergency physicians directly and indirectly; they fill gaps in knowledge by increasing access to addiction-trained subspecialists and improve connectivity to outpatient care that may result in decreased ED utilization and re-visit rates for this patient population. The ED is often the first and only touchpoint to the health system for vulnerable, stigmatized, and marginalized patients such as those with OUD. We are unique in our frontline perspective and accessibility to both the prevalence and extreme consequences of this disease. This gives emergency physicians the opportunity and obligation to lead in health system-level interventions seeking to improve the care of those with OUD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to graciously acknowledge Joan Esbri-Cullen, BS, director of special projects and associate director of the emergency medicine service line at the Mount Sinai Health System, and Andy Jagoda, MD, professor and system chair emeritus of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, for their dedication to creating a space for the expert panel described in this article. The authors would also like to acknowledge which provided funding to assist with hosting the expert panel.

Author Affiliations

- Dr. Hughes is a third-year resident in emergency medicine at the Mount Sinai Hospital and Elmhurst Hospital Center.

- Drs. Khatri, Love, and Shastry are assistant professors of emergency medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Im DD, Chary A, Condella, AL, et al. Emergency department clinicians’ attitudes toward opioid use disorder and emergency department-initiated buprenorphine treatment: A mixed-methods study. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(2):261-271.

- Schoenfeld EM, Soares WE, Schaeffer EM, et al. “This is part of emergency medicine now” – A qualitative assessment of emergency clinicians’ facilitators of and barriers to initiating buprenorphine. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(1):28-40.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2010: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012..

- John WS, Wu LT. Sex differences in the prevalence and correlates of emergency department utilization among adults with prescription opioid use disorder. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(7):1178-1190.

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644.

- Ma J, Bao YP, Wang RJ, et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(12):1868-1883.

- Fairley M, Humphreys K, Joyce VR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(7):767-777.

- Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the Hospital in the 21st Century Opioid Overdose Epidemic: The Addiction Medicine Consult Service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104-112.

No Responses to “Emergency Medicine as Leaders in Care Provision for Patients with Opioid Use Disorder”