A 55-year-old woman with medical history of well-controlled hypertension and renal cell carcinoma, status post-partial nephrectomy, presented to the emergency department (ED) with sudden-onset, 10-out-of-10 chest pain and pressure. She arrived via emergency medical services and was noted to be hypotensive with several blood pressure readings in the 60s/40s mm Hg range en route.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: June 2025 (Digital)Upon arrival, she was normotensive with blood pressure 110/54 mmHg after receiving 250 mL normal saline. The patient was received fentanyl prior to arrival, which improved her pain to a four out of 10. She denied back pain and abdominal pain but endorsed mild nausea. On physical examination, she had no gross neurological deficits. She had a normal cardiopulmonary exam.

There was no edema or discoloration of her lower extremities. She had full strength in bilateral lower extremities but endorsed mild paresthesia in her right leg and calf. It was difficult to palpate pulses in her right lower extremity.

Diagnosis

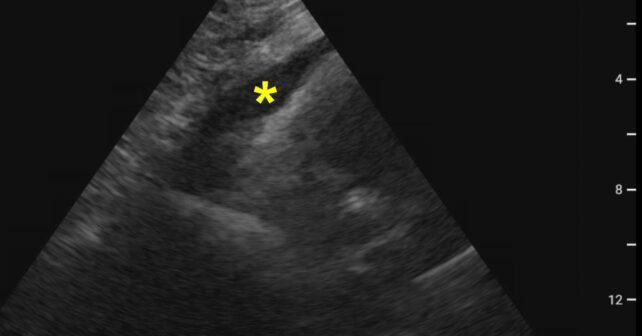

Image 1. Subxiphoid view with yellow star identifying pericardial effusion. (Photos courtesy Ashlee T. Gore, DO. Click to enlarge.)

The patient was well appearing, but given the report of hypotension prior to arrival and history of hypertension, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was used to evaluate for etiology of hypotension in the setting of severe and sudden onset chest pain. Pericardial effusion was identified on subxiphoid view without evidence of tamponade physiology (see Image 1). Parasternal long-axis view identified a dilated aortic root, which strengthened the suspicion for aortic dissection (AD).

Image 2. Parasternal long axis view of dilated aortic root as shown by the yellow circle. Red dotted line outlines dissection flaps seen within the proximal aorta. (Click to enlarge.)

Upon later image review, dissection flaps were seen in the ascending and descending aorta (see Image 2). Once the abnormal POCUS was recognized, a CT dissection protocol with aortic runoff was ordered and the cardiothoracic surgery team was consulted.

Because of the quickly identified aortic dissection, appropriate laboratory tests and medical management were initiated while preoperative CT scanning for surgical planning was obtained. In the interim, the patient experienced worsening right lower extremity pain and she no longer had a palpable pulse in the right leg. By this time the CT imaging had been completed, and the patient was taken to the operating room for repair of significant dissection that included the aortic valve and the entire aortic arch to the level of the bifurcation with a false lumen tracking to the right iliac artery (see Image 3). After a two-week hospital course, she was discharged in stable condition to a short-term rehabilitation facility.

Discussion

In this case, the decision to use POCUS in an otherwise well appearing patient on initial presentation identified the unexpected pericardial effusion on a subxiphoid view. The parasternal long axis demonstrated a dilated aortic root with dissection flaps in the proximal aorta, as well as a dissection flap in the descending aorta. This immediate identification of a proximal aortic dissection facilitated expedited presurgical imaging and appropriate consultation with the cardiothoracic surgical teams. The patient had optimal time to operative repair as POCUS was utilized rather than waiting for progression of symptoms prior to identifying the underlying etiology.

POCUS is a fast and safe option to diagnose acute Stanford Type A aortic dissection (AD). Compared with CT, POCUS has been found to be highly sensitive and specific. It has no adverse effects on treatment initiation time, in-hospital mortality, or mortality within three months of discharge.1

POCUS allows identification of secondary complications of AD such as hemodynamically stable pericardial effusions, which can be found in approximately 33 percent of cases and was identified in this patient.2 Other secondary findings of AD that can be identified on ultrasound include dilated aortic root and aortic regurgitation.2

AD is an emergent condition that typically affects older men with an estimated mortality rate of 40 percent.3 Hypertension is the greatest risk factor for AD. Women often have worse prognosis as they are more likely present atypically, complicating prompt diagnosis and treatment of this emergent condition.2

This patient did not report the typical “ripping” or “tearing” chest and back pain and appeared well overall. Without the prompt application of POCUS, the diagnosis may have been delayed leading to worse outcome; the mortality rate increases with delayed diagnosis.2,4 On chart review, the patient has followed up with cardiothoracic surgery and vascular surgery and is doing well.

Dr. Gore is a second-year emergency medicine resident and Chief Resident of Academics at Wright State University and a Captain in the United States Air Force at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Dr. Gore is a second-year emergency medicine resident and Chief Resident of Academics at Wright State University and a Captain in the United States Air Force at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Ms. Fisher is a third-year medical student at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio.

Ms. Fisher is a third-year medical student at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio.

Dr. Amburgey is an emergency medicine physician at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio. He also serves as the medical director for Hospital EMS and as clinical faculty for the Wright State University department of emergency medicine residency.

Dr. Amburgey is an emergency medicine physician at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio. He also serves as the medical director for Hospital EMS and as clinical faculty for the Wright State University department of emergency medicine residency.

Dr. McKinley is the assistant director of Point of Care Emergency Ultrasound with the Miami Valley Emergency Specialists and a clinical assistant professor at the Wright State University Emergency Medicine residency program in Dayton, Ohio.

Dr. McKinley is the assistant director of Point of Care Emergency Ultrasound with the Miami Valley Emergency Specialists and a clinical assistant professor at the Wright State University Emergency Medicine residency program in Dayton, Ohio.

References

- Wang Y, Yu H, Cao Y, Wan Z. Early screening for aortic dissection with point-of-care ultrasound by emergency physicians: a prospective pilot study. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(7):1309-1315.

- Sayed A, Munir M, Bahbah EI. Aortic dissection: a review of the pathophysiology, management and prospective advances. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2021;17(4):e230421186875.

- Strayer, RJ, Shearer PL, Hermann LK. Screening, evaluation, and early management of acute aortic dissection in the ED. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012 May;8(2):152-157.

- Klompas M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. 2002;287(17):2262.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Case Report: Rapid Diagnosis of Acute Aortic Dissection with POCUS”

October 3, 2025

Nigel HendricksonWas a sternal notch view PoCUS image obtained?