Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is often seen as a primary problem in the emergency department (ED) but can also be an impactful underlying condition for many other presentations. Each time we see a patient with a significant alcohol use history, we need to ask, “Could this be an opportunity to intervene in their alcohol use? What can we offer them in the ED today to manage their AUD? How can we break the cycle of problematic drinking?”

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: February 2026 (Digital)AUD is specifically defined as a “problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress,” characterized by a relapsing and remitting pattern of use, that impacts roughly 29 million individuals throughout the nation.1,2 Based on the DSM-5 criteria, it can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the presence of various symptoms.2

Emergency departments are often the only interaction that many patients have with the health care system. However, we regularly fail to address the consequences of alcohol consumption. AUD is frequently not the primary complaint patients have when seeking treatment at an ED, and it is often not apparent that patients are dealing with this condition, but it may be the underlying cause. This complexity further hampers the accurate identification of patients with this condition who would benefit from appropriate treatment. From 2021 to 2023, alcohol-related ED visits made up about nine million cases, double the number of opioid-related visits.3 This represents a 50 percent rise in alcohol-related visits since the early 2000s.4

But there is precedent that can guide our approach to this problem. Emergency physicians have led the charge in confronting opioid use disorder and reducing overdose deaths through initiating medications like buprenorphine. Emergency physicians can quickly identify and treat alcohol withdrawal syndrome and many of the immediate life-threatening issues associated with alcohol use and can improve upon treating the underlying use disorder. Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder (MAUD) are rarely prescribed in the ED, with data demonstrating that less than 1 percent of AUD patients are initiated on treatment annually.5 Every ED encounter is an opportunity to intervene, screen, educate, and potentially start effective treatment options that can prevent adverse outcomes.

Screening for Alcohol Use Disorder

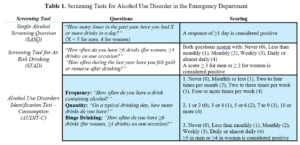

One of the main challenges in treating AUD is properly identifying patients with AUD. Currently, roughly 8 percent of patients who present to the ED are screened.6,7 Multiple tools exist to screen for AUD. Some of the more thorough tools include the DSM-5, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST), and the short MAST (sMAST). While these tools are time-consuming and less likely to be effectively utilized on a wide scale in EDs, the following tools are concise and can be rapidly used to screen for AUD.

The Single Alcohol Screening Question (SASQ) has been found to have both a sensitivity and specificity over 80 percent when applied in the primary care setting.8 While this tool was not intended for the emergency department, its ease of use makes it a suitable option for screening programs. Another screening tool that could be beneficial in the ED is the Screening Test for At-Risk Drinking (STAD), developed from the AUDIT, with reported sensitivities >80 percent and specificities >95 percent in ED settings.9 Either of these tools are short enough to be efficiently implemented in triage or intake, as part of a universal screening program, and are effective at rapidly identifying patients with AUD. The third screening modality we recommend for use in the ED is the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C), which consists of three questions drawn from the full AUDIT. It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 100 percent and a specificity above 85 percent.10 This tool is more reliable but not as brief as the SASQ or STAD. It would be a beneficial tool to use when speaking to patients who have previously screened positive with either of those tests. Any universal screening program will likely use these screening tools in some capacity, but identifying the tools best suited to your institution is most important.

Integrating Screening in the ED

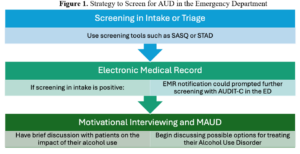

We recommend implementing universal screening in the ED. A short-form screening tool (e.g., SASQ, STAD) should be integrated into the intake or triage process and administered to all patients. Nursing should be involved in facilitating seamless integration. Positive screens should prompt physicians to conduct further screening with the AUDIT-C. For a positive AUDIT-C, physicians can then begin addressing the patient’s AUD and, if interested, can discuss available treatment options with them.

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder

Medications for alcohol use disorder don’t cure the condition. Numerous studies have demonstrated reduced alcohol consumption, cravings, and the risk of relapsing into heavy drinking. Programs designed to prescribe MAUD in the ED have been shown to be both feasible and effective.11 The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) recently published the Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE-4), focusing on the management of AUD.12 In these guidelines, they recommend that anti-craving medication, such as naltrexone or acamprosate, should be prescribed to patients with AUD.12

Medications for AUD include naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, and gabapentin. Several other medications have been used off-label but are unlikely to be prescribed in the ED.

Naltrexone

- Dosing: 50 mg PO daily OR 380 mg IM every four weeks

- Contraindicated in patients with concurrent opioid use, as it may lead to precipitated withdrawal or ineffectiveness.13

- Naloxone challenge: a trial dose of 0.4 mg IV should be given, and the patient observed for signs of withdrawal. There are no data regarding a consensus dose, and dosing has ranged from 0.2 mg to 0.6 mg.13,14

- There is no longer a black-box warning for its use in patients with liver dysfunction, and research has shown that it is safe for use in these patients. But some physicians may feel more comfortable ordering baseline LFTs, although this is not necessary.15

- Evidence:

- Naltrexone was found to have a number needed to treat (NNT) of 11 to reduce the risk of one patient returning to heavy drinking.16

- An emergency department pilot study demonstrated that initiation of 50 mg was feasible and effective, with 33 percent staying engaged in treatment at one month.11

- Patients favored the IM extended-release naltrexone, which was linked to a notable enhancement in quality of life and a decrease in alcohol intake.11,17,18

Acamprosate

- Dosing: 666 mg (two 333 mg tablets) PO TID

- Safe for use in patients with opioid use disorder and liver disease.

- May require up to six pills daily.

- Evidence:

- Found to have an NNT of 11 to prevent one patient from returning to heavy drinking.16,19

- Most effective when patients have already stopped drinking, and has been found to significantly increase the likelihood of maintaining abstinence.16

- Has been shown to be significantly more effective than baclofen for reducing alcohol use.20

Gabapentin

- Dosing: 300-600 mg PO TID

- It is currently FDA-approved as an antiepileptic and for neuropathic pain, but is not currently approved for use in AUD.21

- There are reports of abuse and a potential risk of diversion, but the data are inconclusive.12,22

- Evidence:

- One randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 150 patients demonstrated that gabapentin significantly increased the rates of abstinence, reduced cravings, and heavy drinking days when compared to placebo.23

- Studies have found that it has a lower NNT than acamprosate or naltrexone, at 8, but there has not been any sustained efficacy demonstrated in long-term studies.23

Disulfiram

- Dosing: 250 mg PO daily

- An aversive agent that can induce the “disulfiram reaction:”

- Inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to an accumulation of acetaldehyde, causing flushing, nausea, and vomiting, which may reduce adherence.

- Evidence:

- Has been found to be most effective when adherence is monitored in a supervised setting.24–26

- Studies have demonstrated that disulfiram is comparable to naltrexone for maintaining abstinence and reducing heavy drinking, and that it can help to maintain abstinence in well-selected patients, but RCTs have not shown efficacy.24,27,28

- In a large meta-analysis, evidence for disulfiram was poor, and an NNT could not be calculated.17

Initiating Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder in the ED

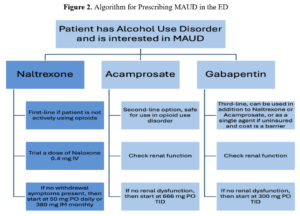

Our recommendation is that patients who screen positive for AUD and are interested in medications to reduce cravings, want to start treatment, do not have a history of opioid use disorder, and are not actively taking opioids, should be initiated on naltrexone. Prior to naltrexone initiation, a “naloxone challenge” should be trialed. This challenge dose of 0.4 mg IV naloxone is given to reduce the risk of naltrexone causing precipitated withdrawal. Trialing this dose of naloxone is not necessary, but it will reduce the risk of precipitating withdrawal, especially if the IM version of naltrexone is given. Following a successful naloxone challenge (absence of precipitated withdrawal), an initial dose of 50 mg PO or the 380 mg IM naltrexone can be administered.

Upon discharge, the patient should be given a prescription for up to 30 days of 50 mg naltrexone if the PO formulation was administered. If the IM version was provided, the patient should be provided with information for a primary care provider, an addiction medicine specialist if available, or outpatient addiction treatment facilities, as well as a follow-up appointment in one month.

While naltrexone is the best option for AUD due to its safety profile, ease of use, and proven effectiveness, if patients are actively taking opioids, then the next best option would be acamprosate. While its large pill burden (six pills daily) makes it difficult to tolerate, systematic reviews have noted that it does significantly reduce heavy drinking.24 In patients who understand the potential adherence challenges, acamprosate is a suitable alternative to naltrexone. Disulfiram is less likely to be initiated in the ED and has yielded inconsistent data, with some studies demonstrating no benefit and others showing a benefit only when used in a supervised program.24,25,27 Gabapentin is occasionally used off-label for the treatment of AUD, and while there are limited studies demonstrating its effectiveness, it is thought to work well in individuals whose alcohol use is triggered specifically by their withdrawal symptoms.12 Yet, gabapentin has been misused throughout the country and has potentially been linked to numerous overdose-related deaths.12,22

We believe that naltrexone is the most effective MAUD, the easiest to initiate in the emergency department, and should be used for patients who are interested in reducing cravings and cutting down on their alcohol intake. The outline below discusses our thought process of how to effectively implement a screening and treatment program for alcohol use disorder in your ED.

1) Develop a universal screening program for Alcohol Use Disorder

- Work with administration, ED staff, and nursing to develop a universal screening program in your ED.

- Use the screening tools and resources that are available and work most effectively in your health care facility.

2) Implement a screening protocol in your ED

-

- Use STAD or SASQ for all patients in intake.

- Use the AUDIT-C for those who have screened positive.

3) Motivational Interviewing

- For patients who had a positive screening or endorsed an interest in reducing their alcohol use, take the time to discuss their alcohol use, and better understand their thoughts about its impact on their health.

4) Gauge Interest in MAUD

- Ask about the patient’s interest in starting potential treatment options such as naltrexone or acamprosate.

5) Discuss Naltrexone

- Offer naltrexone, as it is the best option for treating AUD in most circumstances.

- Ask about the patient’s opioid use history, if the patient has a history of opioid use or current opioid use, then discuss acamprosate.

6) Start MAUD

- Naloxone Challenge: Administer a 0.4 mg IV naloxone dose. It will help to determine if naltrexone would precipitate withdrawal.

- If precipitated withdrawal occurs, then manage with buprenorphine or adjunctive therapies (clonidine, Zofran, loperamide, etc.).

- If no precipitated withdrawal occurs, proceed with treatment.

- Oral: Start with 50 mg PO naltrexone.

- Injectable: Start with 380 mg IM naltrexone.

- If any contraindications to Naltrexone, then initiate acamprosate 666 mg PO TID.

7) Discharge Planning

- If PO naltrexone is administered, then discharge the patient with a 14- to 30-day prescription (50 mg daily).

- If IM naltrexone is given, then arrange follow-up for the patient in one month for the following dose.

- Ensure that all patients have follow-up with a primary care physician (PCP) and addiction medicine physician.

Emergency physicians trailblazed the management of opioid use disorder and the initiation of medications such as buprenorphine. The management of AUD should be no different. The ED is often the only contact between the community and the health care system, and AUD is a condition that impacts numerous individuals seen daily. Each opportunity that we have with a patient with AUD is an opportunity to intervene, discuss resources, and potentially start treatment.

Dr. Imperato is TKTK.

Dr. Greller is an Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Medical Toxicology and Addiction Medicine, at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. He is the director of the Medical Toxicology fellowship, and the co-director of the first combined fellowship in Addiction Medicine and Medical Toxicology. He is a passionate educator and researcher active in local, regional, and national efforts to confront our continued addiction crisis.

Dr. Greller is an Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Medical Toxicology and Addiction Medicine, at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. He is the director of the Medical Toxicology fellowship, and the co-director of the first combined fellowship in Addiction Medicine and Medical Toxicology. He is a passionate educator and researcher active in local, regional, and national efforts to confront our continued addiction crisis.

Dr. Meaden is director of Medical Toxicology Outpatient Services and an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine, Medical Toxicology & Addiction Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

Dr. Meaden is director of Medical Toxicology Outpatient Services and an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine, Medical Toxicology & Addiction Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

References

- Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) in the United States: Age Groups and Demographic Characteristics | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-use-disorder-aud-united-states-age-groups-and-demographic-characteristics

- Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5 | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-use-disorder-comparison-between-dsm

- Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Short Report | Alcohol-related ED visits. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt44498/DAWN-TargetReport-Alcohol-508.pdf

- White AM, Slater ME, Ng G, Hingson R, Breslow R. Trends in Alcohol-Related Emergency Department Visits in the United States: Results from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, 2006 to 2014. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42(2):352-359. doi:10.1111/acer.13559

- Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A Cascade of Care for Alcohol Use Disorder: Using 2015–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Data to Identify Gaps in Past 12-Month Care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286. doi:10.1111/acer.14609

- Uong S, Tomedi LE, Gloppen KM, et al. Screening for Excessive Alcohol Consumption in Emergency Departments: A Nationwide Assessment of Emergency Department Physicians. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(1):E162-E169. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001286

- Cunningham RM, Harrison SR, McKay MP, et al. National survey of emergency department alcohol screening and intervention practices. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(6):556-562. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.004

- Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary Care Validation of a Single-Question Alcohol Screening Test. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):783-788. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0928-6

- Bae SJ, Kim E, Lee JH. Validation of the screening test for at-risk drinking in an emergency department using a tablet computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230:109181. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109181

- van Gils Y, Franck E, Dierckx E, van Alphen SPJ, Saunders JB, Dom G. Validation of the AUDIT and AUDIT-C for Hazardous Drinking in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9266. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179266

- Cowan E, O’Brien-Lambert C, Eiting E, et al. Emergency department–initiated oral naltrexone for patients with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder: A pilot feasibility study. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2025;32(5). doi:10.1111/acem.15059

- Borgundvaag B, Bellolio F, Miles I, et al. Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE-4): Alcohol use disorder and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome management in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2024;31(5):425-455. doi:10.1111/acem.14911

- Singh NM, Daniel K, Balasanova AA. Impact of hospital-administered extended-release naltrexone on readmission rates for patients with alcohol use disorder. Intern Med J. Published online July 10, 2024. doi:10.1111/imj.16467

- Harlow TR, Peters JR, Anderson DL.. Successful Naloxone Challenge Test in a Patient With Atrial Flutter. Psychiatrist.com. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.psychiatrist.com/pcc/naloxone-challenge-test-in-patient-with-atrial-flutter/

- Thompson R, Taddei T, Kaplan D, Rabiee A. Safety of naltrexone in patients with cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 2024;6(7). doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101095

- Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: When are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x

- Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3628

- Murphy CE, Coralic Z, Wang RC, Montoy JCC, Ramirez B, Raven MC. Extended-Release Naltrexone and Case Management for Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;81(4):440-449. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.08.453

- McPheeters M, O’Connor EA, Riley S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2023;330(17):1653-1665. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19761

- Sharma AK, Rikhari P, Shukla AK, Rikhari P. Role of Acamprosate and Baclofen as Anti-craving Agents in Alcohol Use Disorder: A 12-Week Prospective Study. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58174. doi:10.7759/cureus.58174

- Yasaei R, Katta S, Patel P, Saadabadi A. Gabapentin. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed July 31, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493228/

- Kuehn BM. Gabapentin Increasingly Implicated in Overdose Deaths. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2387. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10100

- Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M, Begovic A. Gabapentin Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950

- Bahji A, Bach P, Danilewitz M, et al. Pharmacotherapies for Adults With Alcohol Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Addict Med. 2022;16(6):630-638. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000992

- Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, Aubin HJ. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087366

- Krampe H, Ehrenreich H. Supervised disulfiram as adjunct to psychotherapy in alcoholism treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(19):2076-2090. doi:10.2174/138161210791516431

- Axelrath S. Disulfiram Should Remain Second-line Treatment for Most Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. J Addict Med. 2024;18(6):617-618. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000001360

- Chick J, Gough K, Falkowski W, et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:84-89. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.1.84

- Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel Agents for the Pharmacological Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01670-3

- Klausen MK, Thomsen M, Wortwein G, Fink‐Jensen A. The role of glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) in addictive disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179(4):625-641. doi:10.1111/bph.15677

- Hendershot CS, Bremmer MP, Paladino MB, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025;82(4):395-405. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789

- Lähteenvuo M, Tiihonen J, Solismaa A, Tanskanen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Taipale H. Repurposing Semaglutide and Liraglutide for Alcohol Use Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025;82(1):94-98. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.3599

- Simpson TL, Achtmeyer C, Batten L, et al. Naltrexone augmented with prazosin for alcohol use disorder: results from a randomized controlled proof-of-concept trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2024;59(5):agae062. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agae062

- Rolland B. Baclofen approval in France: A balance between two conceptions of medicine. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(Suppl 1):S28. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.101

- Rose AK, Jones A. Baclofen: its effectiveness in reducing harmful drinking, craving, and negative mood. A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113(8):1396-1406. doi:10.1111/add.14191

- de Beaurepaire R, Jaury P. Baclofen in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: tailored doses matter. Alcohol Alcohol. 2024;59(2):agad090. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agad090

- Phimarn W, Sakhancord R, Paitoon P, Saramunee K, Sungthong B. Efficacy of Varenicline in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: An Updated Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4091. doi:10.3390/ijerph20054091

- Söderpalm B, Lidö H, Franck J, et al. Efficacy and safety of varenicline and bupropion, in combination and alone, for alcohol use disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. 2025;54. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101310

- Johnson B, Alho H, Addolorato G, et al. Low-dose ondansetron: A candidate prospective precision medicine to treat alcohol use disorder endophenotypes. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2024;127:50-62. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2024.06.001

- Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Randall PK, Voronin K. Effect of Naltrexone and Ondansetron on Alcohol Cue–Induced Activation of the Ventral Striatum in Alcohol-Dependent People. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(4):466-475. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.466

- Squeglia LM, Tomko RL, Baker NL, Kirkland AE, McClure EA, Gray KM. A Randomized Controlled Trial of N-acetylcysteine for Adolescent and Young Adult Alcohol Use Disorder. JAACAP.2025;0(0). doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2025.09.025

- Morley K, Arunogiri S, Connor JP, et al. N-acetyl cysteine for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: study protocol for a multi-site, double-blind randomised controlled trial (NAC-AUD study). Published online September 1, 2025. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-091631

- Haass-Koffler CL, Magill M, Cannella N, et al. Mifepristone as a pharmacological intervention for stress-induced alcohol craving: A human laboratory study. Addict Biol. 2023;28(7):e13288. doi:10.1111/adb.13288

No Responses to “Alcohol Use Disorder: Screening Tools and Medications in the ED”