Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 07 – July 2017ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen & Shutterstock.com

In January 2017, the ACEP Board of Directors approved a clinical policy developed by the ACEP Clinical Policies Committee on critical issues in the diagnosis and management of adult psychiatric patients presenting to the emergency department. This policy was published in the April issue of the Annals of Emergency Medicine, can be found on the ACEP website, and has been accepted for inclusion in the National Guideline Clearinghouse.

While the number of mental health-related visits to emergency departments has increased steadily, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds has decreased. Substantial declines in mental health resources have additionally burdened emergency departments with increasing numbers of patients with mental health issues. The “boarding” process for mental health patients in emergency departments nationwide averages seven to 11 hours and often takes more than 24 hours when patients require transfer to an outside facility. New systems and resources need to be made available to better serve mental health patients.

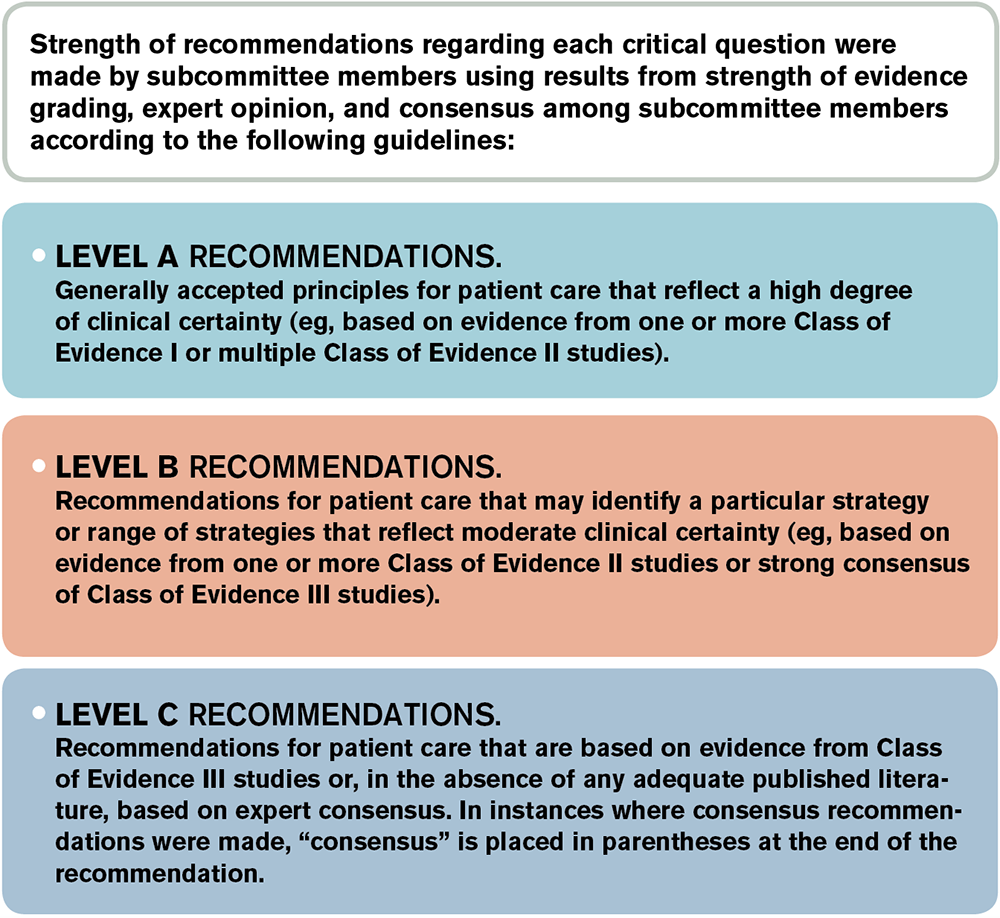

Based on input from the ACEP membership, the committee focused on the critical questions regarding the evaluation and management of adult psychiatric patients in the emergency department. A systematic review of the evidence was conducted, and the committee made recommendations (A, B, or C) based on the strength of evidence (see Table 1). This clinical policy underwent internal and external review during a 60-day open-comment period, and responses were used to refine and enhance this clinical policy.

Table 1. Translation of Classes of Evidence to Recommendation Levels

Critical Questions and Recommendations

Question 1. In the alert adult patient presenting to the emergency department with acute psychiatric symptoms, should routine laboratory tests be used to identify contributory medical conditions (nonpsychiatric disorders)?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A: None specified.

Level B: None specified.

Level C: Do not routinely order laboratory testing on patients with acute psychiatric symptoms. Use medical history, previous psychiatric diagnosis, and physician examination to guide testing.

It is important to note that this is a level C recommendation because of the limited amount of data with sufficient quality to support a higher-level recommendation. However, this should not be interpreted to imply that there is strong evidence supporting the use of laboratory diagnostics in most emergency department mental health patients.

In addition, it is likely that subsets of patients with higher rates of disease (eg, elderly, immunosuppressed, new-onset psychosis, substance abuse) may benefit from routine laboratory testing. Routine urine toxicology testing has not been shown to provide benefit in terms of influencing the management or disposition of ED patients, but it may be helpful for an objective understanding of the patient’s potential substance abuse on transfer to a psychiatric facility.

Question 2. In the patient with new-onset psychosis without focal neurologic deficit, should brain imaging be obtained acutely?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A: None specified.

Level B: None specified.

Level C: Use individual assessment of risk factors to guide brain imaging in the emergency department for patients with new-onset psychosis without focal neurologic deficit (consensus recommendation).

There were no Class I, II, or III studies to answer this question. In the Class X studies that did categorize imaging abnormalities, the percentage of imaging findings described as being clinically relevant, influencing clinical management, or altering diagnosis ranged from 0 percent to approximately 5 percent.

While the number of mental health–related visits to emergency departments has increased steadily, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds has decreased.

Question 3. In adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, can risk-assessment tools in the emergency department identify those who are safe for discharge?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A: None specified.

Level B: None specified.

Level C: In patients presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, physicians should not use currently available risk-assessment tools in isolation to identify low-risk patients who are safe for discharge. The best approach to determine risk is an appropriate psychiatric assessment and good clinical judgment, taking patient, family, and community factors into account.

Class III studies were identified that investigated whether risk assessment can identify patients who are at risk for future self-harm. The designs of these studies were problematic, and no tool has been demonstrated to accurately predict the risk of suicide among patients in the emergency department.

Question 4. In the adult patient presenting to the emergency department with acute agitation, can ketamine be used safely and effectively?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A: None specified.

Level B: None specified.

Level C: Ketamine is an option for immediate sedation of the severely agitated patient who may be violent or aggressive (consensus recommendation).

Management of acutely agitated patients in the emergency department remains a critical issue. Most of these patients can be sedated safely with antipsychotics and/or benzodiazepines. However, there remains a subset of extremely agitated patients for whom this approach will not be effective. These patients have a significant effect on the emergency department staff in terms of time and dedicated resources required to maintain a safe environment for patients and others in the emergency department. Although there is a lack of Class I, II, or III studies establishing the safety and efficacy of ketamine to control acute agitation in the emergency department, the skills set of emergency physicians and their familiarity with the use of ketamine make it a reasonable choice when immediate control of the acutely agitated patient is required for patient and/or staff safety.

Dr. Nazarian is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “ACEP Refines Its Clinical Policy on Psychiatric Boarding”