A 62-year-old female patient presents with fever, cough, and an infiltrate on her chest radiograph. She receives intravenous fluids and antibiotics, but her symptoms worsen, eventually requiring intubation for respiratory decompensation and vasopressors for presumed septic shock. The intensive care unit is full, so the patient remains in the emergency department. During this time, her condition worsens, and she develops new renal and hepatic injury. You wonder if there is something you may be missing. Could this patient have abdominal compartment syndrome? If so, how do you test for it, and what are the next steps in management?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 10 – October 2020Discussion

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is a disease that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.1–3 However, it is not often considered in the emergency department. With high rates of ED boarding in many areas, it is essential for the ED clinician to be aware of this disease and monitor for it.

ACS is similar to limb compartment syndrome in that there is excessive pressure within a closed space (ie, the abdominal compartment), resulting in damage to the surrounding structures. This exists as part of a continuum beginning with elevated intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and ending with organ dysfunction (see Table 1). There are numerous causes of ACS, but they mainly fall into four general categories: reduced abdominal wall compliance (eg, abdominal surgery, obesity), increased abdominal contents (eg, large-volume ascites, hemoperitoneum), increased intraluminal contents (eg, ileus, gastroparesis), or capillary leak (eg, sepsis, pancreatitis).4,5

Table 1: Grading of Intra-Abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

| IAH Grade | Intra-Abdominal Pressure |

|---|---|

| Grade I | 12–15 mm Hg |

| Grade II | 16–20 mm Hg |

| Grade III | 21–25 mm Hg |

| Grade IV | >25 mm Hg |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | Sustained IAP >20 mm Hg with new organ dysfunction |

IAH, intra-abdominal hypertension; IAP, intra-abdominal pressure

Obtaining a relevant history may prove challenging because most patients with ACS are critically ill, and many are intubated. For patients who can provide a history, worsening abdominal pain, abdominal distension, or difficulty breathing (particularly when supine) may be reported.6,7 The physical examination is also limited in these patients; studies demonstrate a sensitivity of 40–60 percent and a specificity of 80–94 percent for ACS diagnosis.8,9 Abdominal distension and the absence of bowel sounds are associated with ACS, but their absence cannot exclude it.5 Therefore, clinicians should remember this condition for critically ill patients with worsening or refractory hypotensio and those with new organ failure.

Laboratory studies may demonstrate evidence of severe organ dysfunction, including elevations in lactate, creatinine, and liver markers.10 If obtained, a computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis may demonstrate an increased anteroposterior diameter, inferior vena cava collapse, diaphragm elevation, renal vessel compression, thickened bowel wall, pneumoperitoneum, or inguinal hernias bilaterally.11–13 However, neither the history and physical examination nor advanced imaging is sufficient to exclude the diagnosis. Therefore, clinicians who are concerned about ACS should measure the IAP (see Table 2).

Table 2: Measuring IAP in Suspected ACS

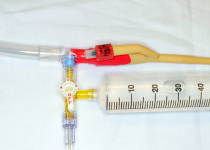

| 1. Gather the following supplies: Foley catheterization kit, sterile gloves, 60-mL syringe filled with 25 mL of saline, curved hemostat, 1-L bag of fluid, and arterial line tubing and transducer kit (see Figure 1A). χαρετ−ριγητ |

| 2. Insert Foley catheter to drain all urine. |

| 3. Place the patient in the supine position and provide appropriate analgesia. |

| 4. Set up an arterial line, and prime with a 1-L bag of fluid. |

| 5. Attach the stopcock to a 60-mL syringe filled with saline at the end of the arterial line tubing. |

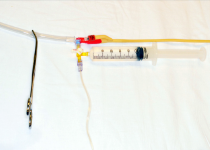

| 6. Clean the access port with an alcohol swab, and attach a three-way stopcock to the catheter access port (see Figure 1B). χαρετ−ριγητ |

| 7. Zero the pressure transducer at the level of the bladder, located at the iliac crest in the midaxillary line. |

| 8. Clamp the drainage bag of the Foley catheter just distal to the aspiration port. |

| 9. Instill a maximum of 25 mL of warm sterile saline into the bladder (see Figure 1C). χαρετ−ριγητ |

| 10. Turn the stopcock so the off position is now directed toward the 60 mL syringe. The syringe may now be removed. |

| 11. Unclamp the distal Foley catheter to allow air in the proximal tubing to pass into distal tubing. The tubing should then be clamped again. |

| 12. Before obtaining the IAP value, at least 30 seconds should pass with fluid in the bladder to ensure the detrusor muscle relaxes. |

| 13. After this period, obtain the bladder pressure at end-exhalation. |

| 14. Once the IAP is obtained, unclamp the Foley catheter. |

IAP, intra-abdominal pressure; ACS, abdominal compartment syndrome;

Adapted from Gottlieb et al.5

FIGURE 1A

FIGURE 1B

FIGURE 1C

PHOTOS: Michael Gottlieb and Brit Long

Although multiple methods of IAP measurement have been proposed, intravesicular measurement generally preferred. As the name suggests, this measurement is obtained by placing a Foley catheter into the bladder. When measuring IAP, the patient should be supine and relaxed to avoid artificially increasing the IAP measurements.5,10 Ensure the patient’s pain is adequately controlled and measure the pressure at end-expiration.14 Clinicians should use warm saline to avoid detrusor muscle spasm, and no more than 25 mL of fluid should be instilled to avoid false elevations of IAP.14 ACS is defined as an IAP >20 mm Hg with evidence of organ dysfunction.14

Treatment of ACS focuses on improving end-organ perfusion by reducing IAP. This includes four main steps: 1) evacuating intraluminal and intraperitoneal contents, 2) improving abdominal wall compliance, 3) optimizing intravascular fluid therapy, and 4) early surgical consultation for possible surgical decompression.

Ileus and luminal distension are common in patients with ACS.15,16 Nasogastric or orogastric tubes can reduce gastric distension, while prokinetc agents (eg, metoclopramide, erythromycin) may help reduce intraluminal contents.14,17 Extraluminal pathologies (eg, ascites, hemoperitoneum, pneumoperitoneum) may also require drainage, which can be performed percutaneously or through operative drainage.18–20

Adequate analgesia and sedation should be provided because pain and sedation can further increase IAP. If the patient is intubated, clinicians should aim for as low positive end-expiratory pressure and plateau pressures as the oxygen saturation allows.10,16 Paralysis can also be used as a temporary bridge for refractory cases while awaiting surgical decompression.21–23

Clinicians should avoid excessive fluid administration because third spacing will worsen existing ACS.10,16 If patients are hypotensive or septic, early vasopressor and inotropic therapy may be preferable in these patients; norepinephrine and dobutamine have the best literature support in treating ACS-associated hypotension.24–27

In cases that are refractory to the above interventions, surgical decompression may be warranted. Therefore, it is important to consult a surgeon early in the management of suspected ACS patients.

Case Resolution

You suspect ACS and assess the IAP using a Foley catheter. The IAP is 25 mm Hg, and a repeat creatinine level is significantly elevated. You place an orogastric tube, administer metoclopramide, ensure the patient is adequately sedated, and consult a surgeon for possible operative management. The patient is taken to the operating room for surgical decompression.

Dr. Gottlieb is associate professor, ultrasound division director, and ultrasound fellowship director in the department of emergency medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Dr. Long is an emergency physician in the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

References

- Malbrain MLNG , Chiumello D, Pelosi P, et al. Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(2):315-322.

- Vidal MG, Ruiz Weisser J, Gonzalez F, et al. Incidence and clinical effects of intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1823-1831.

- Murphy PB, Parry NG, Sela N, et al. Intra-abdominal hypertension is more common than previously thought: a prospective study in a mixed medical-surgical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):958-964.

- Sugrue M, De Waele JJ, De Keulenaer BL, et al. A user’s guide to intra-abdominal pressure measurement. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015;47(3):241-251.

- Gottlieb M, Koyfman A, Long B. Evaluation and management of abdominal compartment syndrome in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2019;S0736-4679(19)30830-3.

- Carr JA. Abdominal compartment syndrome: a decade of progress. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(1):135-146.

- Hecker A, Hecker B, Hecker M, et al. Acute abdominal compartment syndrome: current diagnostic and therapeutic options. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401(1):15-24.

- Kirkpatrick AW, Brenneman FD, McLean RF, et al. Is clinical examination an accurate indicator of raised intra-abdominal pressure in critically injured patients? Can J Surg. 2000;43(3):207-211.

- Sugrue M, Bauman A, Jones F, et al. Clinical examination is an inaccurate predictor of intraabdominal pressure. World J Surg. 2002;26(12):1428-1431.

- Papavramidis TS, Marinis AD, Pliakos I, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome – intra-abdominal hypertension: defining, diagnosing, and managing. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(2):279-291.

- Patel A, Lall CG, Jennings SG, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(5):1037-1043.

- Sugrue G, Malbrain MLNG, Pereira B, et al. Modern imaging techniques in intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome: a bench to bedside overview. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2018;50(3):234-242.

- Bouveresse S, Piton G, Badet N, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome and intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients: diagnostic value of computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(7):3839-3846.

- Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, et al. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1190-1206.

- Cheatham ML. Abdominal compartment syndrome: Pathophysiology and definitions. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:10.

- Sosa G, Gandham N, Landeras V, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Dis Mon. 2019;65(1):5-19.

- Hunt L, Frost SA, Hillman K, et al. Management of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome: a review. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2014;8(1):2.

- Savino JA, Cerabona T, Agarwal N, et al. Manipulation of ascitic fluid pressure in cirrhotics to optimize hemodynamic and renal function. Ann Surg. 1988;208(4):504-511.

- Corcos AC, Sherman HF. Percutaneous treatment of secondary abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma. 2001;51(6):1062-1064.

- Liang YJ, Huang HM, Yang HL, et al. Controlled peritoneal drainage improves survival in children with abdominal compartment syndrome. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:29.

- De Waele JJ, Benoit D, Hoste E, et al. A role for muscle relaxation in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome? Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(2):332.

- Deeren DH, Dits H, Malbrain MLNG. Correlation between intra-abdominal and intracranial pressure in nontraumatic brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1577-1581.

- De Laet I, Hoste E, Verholen E, et al. The effect of neuromuscular blockers in patients with intra-abdominal hypertension. Intensive Care Med. 2007 Oct;33(10):1811-1814.

- Zhang H, Smail N, Cabral A, et al. Effects of norepinephrine on regional blood flow and oxygen extraction capabilities during endotoxic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(6):1965-1971.

- Agustí M, Elizalde JI, Adàlia R, et al. Dobutamine restores intestinal mucosal blood flow in a porcine model of intra-abdominal hyperpressure. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(2):467-472.

- Krejci V, Hiltebrand LB, Sigurdsson GH. Effects of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and phenylephrine on microcirculatory blood flow in the gastrointestinal tract in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):1456-1463.

- Peng ZY, Critchley LA, Joynt GM, et al. Effects of norepinephrine during intra-abdominal hypertension on renal blood flow in bacteremic dogs. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):834-841.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Abdominal Compartment Syndrome in the Emergency Department”