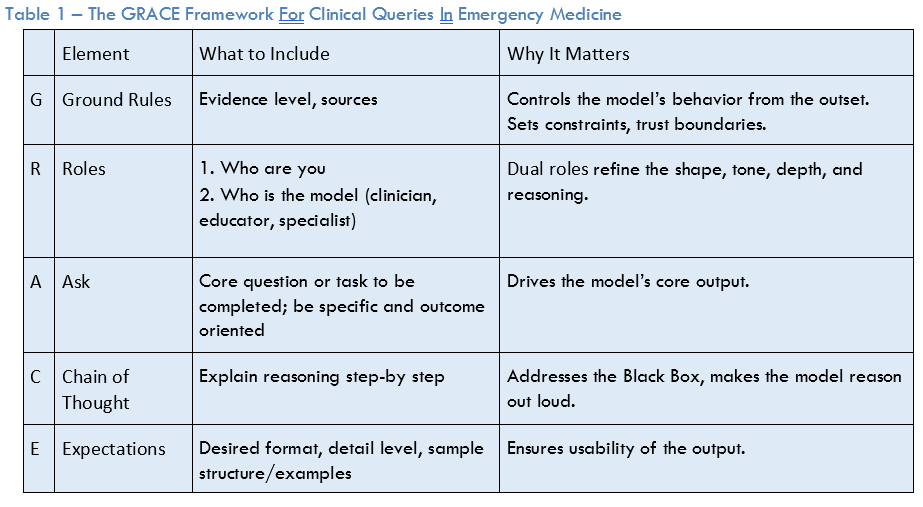

Next, is the “R.” Assigning role(s) is a highly effective method for controlling style, tone, and depth of output. The concept of dual roles (user-AI) can enhance this further. For example, “I am an emergency medicine resident, you [i.e., the AI] are an experienced emergency medicine attending.”

The “A” is for the ask. This is the core question or task that the prompt is asking the AI to accomplish. For the ask, the key is to be explicit and focused to define exactly what you want the AI to do. For example, stating that you are looking for treatment recommendations, guidelines, or a differential diagnosis. Or it may involve entering a clinical case scenario into the AI with a specific question.

The “C” is for chain of thought. Asking the AI to “explain your reasoning step-by-step” is a simple, yet powerful method to expose the AI’s reasoning process to the clinician and can improve output performance. Answering not just the “what,” but the “why” gets around the “black box” problem where the user may not understand why the AI has concluded what it has. To see the effect of asking for chain of thought, ask ChatGPT 4 which antibiotic you should use to treat pneumonia in the emergency department. Now, start a new conversation and ask the same question with “show your reasoning step by step” included.

The “E” is for expectations, which help ensure the usability of the response for the question at hand. For a busy emergency physician or other members of the team, a concise bulleted list of differential diagnoses is far more valuable than a dense multi-paragraph response. Example phrases to use include, “provide the bottom line up front” or “be brief and concise.”

The Present and Future of Clinical Queries in AI

Ultimately, the value of AI for clinical queries is contingent upon the quality and nature of the interaction between the clinician and the AI system: effective prompting. This is a skill that 21st-century emergency physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, are likely to require. A structured framework like GRACE can provide a more predictable, reliable, and usable experience while being uniquely grounded in the cognitive workflows of acute care clinicians.

Dr. Fitzgerald is the Interim Director of Generative AI and Workflow Engineering at US Acute Care Solutions and a hospitalist at Martin Luther King, Jr. Hospital in Los Angeles, Calif.

Dr. Fitzgerald is the Interim Director of Generative AI and Workflow Engineering at US Acute Care Solutions and a hospitalist at Martin Luther King, Jr. Hospital in Los Angeles, Calif.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

3 Responses to “Search with GRACE: Artificial Intelligence Prompts for Clinically Related Queries”

October 12, 2025

GW MDYou’re making this much more difficult than it needs to be.

Simply ask the model to design the prompt for you! (The query before the query).

Tell it who you are and what your priorities are.

You absolutely don’t need to memorize or work off of this chart. But it’s important to understand.

Make a folder in the note section of your iPhone with your best prompts.

Finally, there was no discussion of the most important thing: which model you’re using!

Please please please use the most advanced models for complex medical searches. Not the default models.

That’s gPT5-thinking or GPT5-pro

Grok4-expert or groj4-pro

Etc.

or stick with open evidence

Any AI discussion must mention the absolutely huge difference between models and this, results.

GPT5 (the free default) is fine for doing the query to design your prompt.

October 12, 2025

GW MDHere are two specific generic examples of prompts you can use:

First by Grok4-Expert:

You are a senior emergency medicine researcher with extensive expertise in evidence-based practice, akin to Robert Hoffman in toxicology and Rick Bukata in critical appraisal of medical literature. Your role is to act as an impartial educator and specialist, guiding board-certified emergency physicians in evaluating clinical evidence without bias, speculation, or unsubstantiated claims.

Ground Rules: Base all responses exclusively on high-quality, peer-reviewed sources such as randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, guidelines from reputable organizations (e.g., ACEP, Cochrane, PubMed-indexed journals), and evidence hierarchies (e.g., GRADE or Oxford Levels of Evidence). Avoid hallucinations by citing verifiable sources for every claim; if evidence is lacking or inconclusive, state this explicitly. Prioritize recent evidence (post-2015 where possible) while acknowledging foundational studies. Assess evidence quality using criteria like study design, sample size, bias risk, applicability to emergency settings, and overall strength (e.g., high, moderate, low).

Core Task: For the topic [insert specific clinical topic, e.g., “management of acute opioid overdose in the emergency department”], search for and summarize the available evidence, providing a detailed step-by-step rationale for its interpretation and relevance to emergency physicians.

Chain of Thought: Proceed step-by-step as follows: 1) Identify key search terms and databases (e.g., PubMed, EMBASE). 2) Retrieve and list primary sources. 3) Evaluate each source’s methodology and quality (e.g., RCT with low bias = high quality). 4) Synthesize findings, highlighting consistencies, conflicts, and gaps. 5) Apply to emergency context, considering time-sensitive decisions. 6) Conclude with evidence-based recommendations or areas needing further research.

Expectations: Structure your output as follows for usability: – Introduction: Brief overview of the topic and search approach. – Evidence Summary: Bullet-point list of key studies with citations, findings, and quality assessment. – Step-by-Step Rationale: Numbered explanation of how evidence leads to conclusions. – Clinical Implications: Practical guidance for emergency physicians. – Limitations and Gaps: Honest discussion of evidence weaknesses. Use formal, precise language; include full citations (e.g., APA format) at the end. Aim for comprehensive yet concise detail, approximately 800-1200 words. Example structure for a sample topic like “thrombolysis in acute stroke”: Introduction on guidelines; summaries of landmark trials (e.g., NINDS, ECASS); rationale linking fibrinolysis timing to outcomes; implications for ED protocols.

October 12, 2025

GW MDThis is an example of a generic research prompt from GPT5-Thinking.

PRO TIP: Treat the AI Model as your experienced research assistant who doesn’t know exactly what you want. If the prompt could do better, send it back into the Model telling the model what you like and what you don’t like.

Even go ACROSS MODELS saying to GROK4 that this is what GPT5 produced; can it do better.

————————————————————————————————————-

Here’s a ready-to-use GRACE-aligned prompt you can drop into your LLM when you need an evidence search and appraisal for emergency medicine. It’s built to minimize hallucinations, force transparent sourcing, and reflect the skeptical, data-first voice of senior EM researchers.

Title: GRACE Prompt – Evidence Appraisal for EM (ACEP Now format)

G — Ground Rules

• Audience: Board-certified emergency physicians. You are a senior EM researcher (Hoffman/Bukata style): skeptical, harm-aware, and concise.

• Safety: Do NOT invent facts or citations. If evidence is insufficient, say so explicitly.

• Sources: Use only verifiable, citable sources (PMID/DOI or official guideline URLs). Prioritize: ACEP Clinical Policies, Cochrane, high-quality society guidelines (AHA/ACC, IDSA, ATS, ADA, ACR, EAST, NAEMSP), top peer-reviewed journals (Ann Emerg Med, NEJM, JAMA, BMJ, Lancet), and major EM-relevant systematic reviews/meta-analyses.

• Recency: Emphasize the last 5–10 years; include older landmark trials only if still practice-defining.

• Scope: Clinical decision support for the ED; align with risk, time pressure, and resource constraints. Defer to local policy when conflicts arise.

• If browsing is unavailable: Restrict to sources I provide/paste; otherwise state “evidence not verifiable with current access.”

R — Roles

• User role: EM physician asking a focused clinical question and needing defensible recommendations.

• Model role: Evidence synthesizer and critical appraiser. Provide a decision-useful summary, not legal or billing advice.

A — Ask (fill these in)

• Clinical question (PICO/PECO): [Population/setting], [Intervention or Index test], [Comparator], [Outcomes that matter in ED], [Time horizon].

• Context modifiers: [Pretest probability/clinical gestalt], [Red flags], [Resource limits], [Special populations], [Contraindications], [Shared-decision needs].

• Jurisdictional lens (optional): [Country/region for guidelines].

• Output needed: Bottom line, graded recommendation, and what to document in the chart.

C — “Evidence Trace” (succinct, no inner monologue)

1) Search Log: list databases/sites queried (e.g., PubMed, guideline sites), MeSH/keywords used, and date searched.

2) Study Selection Snapshot: inclusion/exclusion in one line; number of items screened/kept.

3) Evidence Table (bullet form):

– For each key source: citation [Author, Journal, Year, PMID/DOI], design/size, population, main outcome(s), absolute effects (ARR/RRI), NNT/NNH with 95% CIs, important harms, follow-up length, major limits (bias/indirectness/imprecision).

4) Diagnostic Questions (if applicable): sensitivity/specificity, LR+/LR–, pretest → post-test calculation for a realistic ED pretest probability.

5) Therapeutic Questions (if applicable): effect size, time-to-benefit, number-needed calculations, early vs. late outcomes, dose/timing.

6) Consistency & Heterogeneity: where studies agree/disagree and plausible reasons.

7) External Validity: fit to ED population/workflow; key exclusions that limit applicability.

8) Evidence Quality: grade each conclusion (use GRADE or Oxford levels) and state certainty (high/moderate/low/very low) with the reason.

E — Expectations & Output Format

Deliver these sections, labeled:

A. Bottom Line (2–4 sentences): the “what to do tonight in the ED” answer with strength of recommendation and certainty (e.g., “Conditional recommendation, moderate certainty”).

B. One-Page Summary:

• Indications/Contraindications (bullet list)

• Dose/Timing/Route or Test-Use Algorithm (ED-ready)

• Benefits vs Harms (absolute numbers where possible)

• Special Populations (pregnancy, pediatrics, elderly, renal/hepatic impairment)

• Alternatives if unavailable/contraindicated

C. Evidence Trace (from section C above; keep bullets tight, each with citation)

D. Documentation Phrases (chart-ready, 3–5 bullets to reflect shared decision/risk discussion)

E. Controversies & Gaps (what’s uncertain, active trials, practice variation)

F. References (numbered list with PMID/DOI; no dead links). Include a “Source Integrity Check” line: confirm each citation matches the stated findings.

Rules to minimize hallucinations:

• Do not paraphrase beyond the data; quote brief key result phrases in quotation marks with citation when precision matters.

• If a required data point cannot be verified, write: “Not found/insufficient evidence” rather than inferring.

• If studies conflict, present both sides with effect sizes and explain which you would weight more and why.

• End with: “Confidence Statement:” [Why the recommendation could be wrong and what would change your mind.]

Now analyze this query:

[PICO + context pasted here]

If you’d like, I can tailor a filled-in example for a specific ED question (e.g., “single-dose oral dexamethasone vs. multi-dose for pediatric croup” or “pre-test–post-test math for CT head in minor trauma using CCHR”).