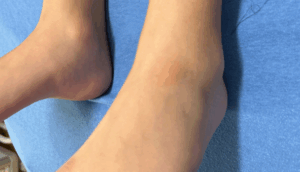

A 10-year-old boy with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department (ED) with fevers for five days. Symptoms began with temperatures as high as 104⁰F with ketones in the urine noted on a home test. The patient did not have any associated symptoms. His mom stated that he had a limp that began after a dance rehearsal a few days ago, though no trauma was reported, and had since improved. The patient’s vaccination record was up to date. On exam, the patient was noted to have a slightly red, minimally tender, flat lesion of the left ankle which was not warm to touch (Image 1). His gait was normal. He had a fever but otherwise the rest of the vital signs were normal. Laboratory tests and an X-ray of the ankle were obtained. Results included: WBC of 6.4 x 103 /µL, CRP of 2.5 mg/L (ref <4.90 mg/L), and procalcitonin of 2.24 ng/mL (ref 0.00-0.50 ng/mL). The chemistry panel was normal with blood glucose 81 mg/dL and no evidence of metabolic acidosis. The ankle X-ray showed soft tissue swelling without acute osseous abnormality. Blood cultures were sent. The patient was presumed to have cellulitis given skin discoloration and swelling on X-ray. He was given ceftriaxone in the ED but developed a rash,and was discharged on doxycycline.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: December 2025 (Digital)The following day, blood cultures were positive for Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). The patient was called to return and subsequently admitted for bacteremia. An MRI of the ankle was obtained, which revealed osteomyelitis with a small amount (1 mL) of fluid along the anterior distal tibia. Patient was subsequently taken to the operating room with orthopedics for drainage and decompression. Following this, he continued to improve with IV antibiotics and was subsequently discharged on a four-week course of cefazolin per the request of the consulting infectious disease team. Noting the patient’s adverse reaction to ceftriaxone, the patient was initially monitored when given cefazolin as there was potential for cross reactivity, but he tolerated it well without reaction.

Osteomyelitis is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal infections plaguing pediatric populations.1 Pathogenically it can develop by hematologic spread or via direct inoculation with significant penetrating trauma or surgery.1 The most common culprit is Staphylococcus aureus, as in our case. Presentation of osteomyelitis is varied and dependent on the extent of the infection. On one end of the spectrum, it can be a localized infection present on a single metaphysis free of associated symptoms. The other extreme is severe multifocal infection accompanied by septic shock.2

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

3 Responses to “Case Report: Five Days of Fever”

December 21, 2025

Gabe WilsonA few learning points:

1. The “Dissociated” Inflammatory Markers

The most striking feature here was the discordance between the CRP (2.5 mg/L) and the Procalcitonin (2.24 ng/mL).

• The Trap: Relying solely on the normal CRP led to the initial exclusion of osteomyelitis. In approximately 2–5% of AHO cases, the CRP can be normal on admission, particularly if the organism is less virulent (e.g., Kingella—though not the case here) or in early/walled-off S. aureus infections.

• The Clue: The Procalcitonin was the “truth-teller.” A PCT >2.0 in a pediatric patient without a clear source is highly specific for invasive bacterial infection (bacteremia/sepsis) and should trigger a hunt for the source regardless of the CRP.

2. The “Phantom” Limp

The history of a limp that “improved” and a normal gait in the ED is a common confounder in pediatric osteomyelitis.

• Children often guard intermittently.

• The “lesion” on the ankle (initially thought to be the result of the dance shoe) was likely the cause (portal of entry) or a manifestation (septic embolus/Janeway lesion) of the intravascular infection.

3. T1DM as a Risk Factor (co-morbidities, co-morbidities, co-morbidities – ALWAYS be super suspect of more advanced or unusual disease)

Even with a normal glucose (81 mg/dL) and no DKA, the patient’s Type 1 Diabetes history is relevant.

• It places the patient at higher risk for invasive S. aureus infections (via pump sites/CGM or altered neutrophil function).

• It may also blunt the typical febrile/inflammatory response, contributing to the confusing presentation.

December 21, 2025

Gabe WilsonOne additional point:

DIAGNOSTIC INCONGRUITY/ANCHORING BIAS

I have yet to see such a subtle cellulitis in someone mounting a fever of 104F. With that fever, there would be a correspondingly large area of typical indurated, very erythematous, tender, warm skin.

A subtle presentation on the derm exam combined with a fever of 104F does not, in my experience, align with a diagnosis of cellulitis.

December 22, 2025

STEPHEN J. VAN CLEAVELimping is not common with cellulitis. So with joint pain in a diabetic child, you need CT or MRI of the affected joint, not plain X-ray.