Terms such as “confusion,” “altered mental status,” or “not acting right,” are frequently used and invariably make their way into emergency department (ED) documentation. The terms are often used interchangeably, casually, and without much thought. But here’s the issue: none are diagnoses; they’re symptoms. Using these terms haphazardly as diagnostic surrogates can delay care, obscure critical illness, and leave dangerous gaps in reasoning and documentation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: January 2026If we are to start improving outcomes for our aging patients with cognitive impairment, we need to start by using the right vocabulary. Delirium is not just another way of saying “confused.” It’s a well-defined clinical syndrome characterized by acute onset, a fluctuating course, impaired attention, and disturbed awareness that arises from an underlying physiological insult.1 Delirium is identifiable, screenable, and often reversible.

By contrast, encephalopathy is a pathobiological process, referring to diffuse brain dysfunction caused by metabolic, toxic, infectious, or other systemic disturbances.1 Encephalopathy has a broad pathogenesis, and delirium is what the culmination of that pathogenesis might look like clinically. Recognizing this distinction isn’t purely academic — it’s actionable. Once we name it delirium (not just confusion), we can screen for it, work it up, and treat it.

Delirium in the ED

Delirium affects as much as 15 percent of older adults in the ED.2,3 Despite this, emergency physicians do not recognize delirium in about half or more of cases. One prospective study of about 1,500 patients aged 65 or older found that nurses missed delirium in 55 percent of cases, and physicians in about 50 percent.4

Sending patients home with delirium unrecognized is not a minor oversight and comes with serious consequences. A recent retrospective study of 22,940 ED visits showed that patients discharged with delirium experienced nearly three times the 30‑day mortality rate (adjusted relative risk 2.86) and significantly higher rates of return ED visits compared with those discharged without delirium.5 Beyond mortality, unrecognized delirium is linked to prolonged hospital stays, increased risk for institutionalization, and long-term functional decline.3,6

Efficient Screening

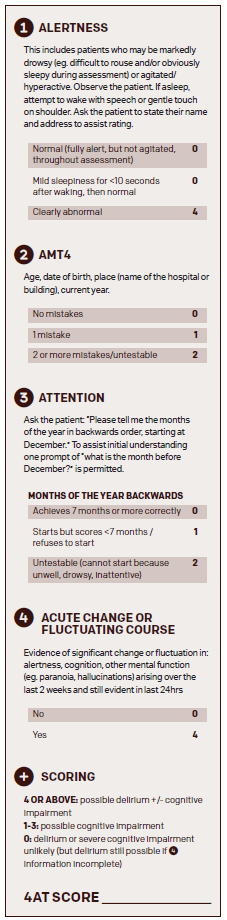

Once delirium is suspected, we need a validated, rapid tool to screen for it. The 4AT rapid clinical test is ideal as it assesses alertness, attention, acute change/fluctuation, and cognition.7 The test takes less than two minutes, is training-free, and demonstrates approximately 88 percent sensitivity/specificity in adults.8,9 The tool also outperforms Confusion Assessment Method-based screens in ED environments.10 A score of four or greater indicates delirium; a score of one to three suggests cognitive impairment and a potential need for further observation.7

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “A Practical Guide to Diagnosing Delirium and Acute Cognitive Change in the ED”