Despite advanced airway management options like mask ventilation supraglottic airways, there is still a role for cricothyrotomy in the ED. Here are some tips on when to use cricothyrotomy and tricks on performing the surgery

Crics should be considered a first-line approach in situations of the “surgically inevitable airway.” These are cases in which mask ventilation, supraglottic airways (LMA/King LT), and passive oxygenation will not work.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 02 – February 2014

Part one of a two-part series.

Thirty years ago, when airway management options only included direct laryngoscopy and mask ventilation, cricothyrotomy was used routinely if laryngoscopy and mask ventilation failed. Now, the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and other supraglottic airways allow us to rescue ventilate in 95 percent of mask-ventilation failures. Video laryngoscopes (and fiber optics via LMA) now allow intubation in many instances of difficult or impossible direct laryngoscopy. New techniques of pre-oxygenation, positioning, and apneic oxygenation (ie, nasal oxygen during efforts securing a tube, or NO DESAT) can markedly prolong safe apnea. Better ventilation strategies (low volume, low pressure, positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] valves, nasal cannula with bag-valve-mask [BVM] use) improve oxygenation and also reduce the risk of regurgitation. We are no longer bound to one attempt at intubation before hypoxemia leads to desperate bagging and a surgical airway.

What is the role for cricothyrotomy in this era of many devices and better oxygenation and ventilation techniques? Crics should be considered a first-line approach in situations of the “surgically inevitable airway.” These are cases in which mask ventilation, supraglottic airways (LMA/King LT), and passive oxygenation will not work. Surgically inevitable airways are trauma cases in which a surgical airway will be required as part of the patient’s near-term management. The prototypical example is a severe blast injury to the lower face. Distorted anatomy coupled with blood/vomit is a serious problem—it is bad for laryngoscopy, mask ventilation, LMA, and King LT use, as well as passive oxygenation via mouth or nose. Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) must be avoided in these cases; an awake surgical airway (with or without ketamine) is the safest option. Not all instances of distorted anatomy require an immediate surgical airway; without bleeding or vomit, an awake, fiber-optic, or other non-RSI technique may be worth trying in angioedema and other oral-pathology circumstances. Because there is no guarantee of being able to rescue ventilate, a surgical approach may be emergently needed if the patient deteriorates. Instances involving massive fluids (blood/vomit) even without distorted anatomy may trigger a surgical airway when epiglottoscopy and other landmark identification are impossible along with the inability to oxygenate and/or ventilate. If intubation fails in cases with intrinsic laryngeal pathology (eg, laryngeal tumor, high-grade laryngeal fracture), a surgical airway is necessary below the level of the pathology (ie, tracheotomy instead of a cricothyrotomy).

Once the operator has crossed the decision point, a surgical airway is inevitable; patient outcome hinges on speed. To ensure success, one must be able to reliably identify landmarks and have a methodical, step-by-step approach.

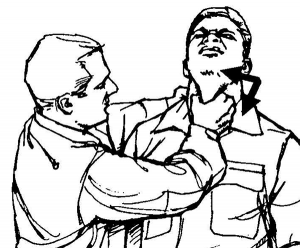

Instead of using the tip of the index finger to feel for landmarks, palpate the laryngeal framework using the whole hand with what I call the “laryngeal handshake.”

The Technique

The traditional method of finding the cricothyroid membrane relies on palpation of the thyroid prominence (Adam’s apple) and the gap between the lower thyroid cartilage and the cricoid ring. This works well in thin males but not when there is significant neck fat and musculature. In women, the thyroid lamina is smaller and has a shallower angle; there is no thyroid prominence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Female versus male external anatomy: The thyroid prominence is evident in the male, whereas the thyroid and cricoid have equal prominence in a female.

Female versus male external anatomy: The thyroid prominence is evident in the male, whereas the thyroid and cricoid have equal prominence in a female. [/caption]Instead of using the tip of the index finger to feel for landmarks, palpate the laryngeal framework using the whole hand with what I call the “laryngeal handshake”(see Figure 2).

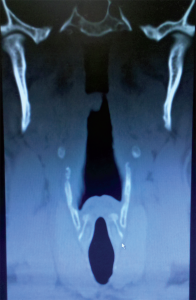

The hyoid, thyroid, and cricoid form a rhomboid structure and move as a unit from side to side (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The “laryngeal handshake,” from left to right: 1) hyoid, 2) thyroid, 3) cricoid, and 4) palpation of cricothyroid membrane.

Instead of feeling for the thyroid prominence, palpate the broad thyroid lamina. When the front of the neck does not give certainty of location, I have found that palpating the firm lamina of the thyroid and moving the whole laryngeal framework from side to side will consistently confirm the landmarks.

Figure 3.

CT imaging of the larynx in a coronal projection showing the epiglottis; the piriform recesses lateral to the epiglottis; the hyoid (bright dots); thyroid lamina; and, lowest and most medial, the cricoid. The vocal cords are at the inferior aspect of the thyroid cartilage. Note the rhomboid shape from the hyoid to the thyroid and cricoid and that the lower thyroid encircles the cricoid.

It does not take a lot of force to appreciate landmarks or rock the larynx side to side. Palpation of the laryngeal framework has been taught as a close combat technique (when used with maximum force) to perform a “tracheal choke” (see Figure 4).

I initiate the laryngeal handshake with my dominant right hand (see Figure 5). Ergonomically, I prefer to stand on the patient’s right side (at the thorax) so that when holding the scalpel, I can rest my cutting hand on the sternum. (We will address sternal stabilization in part two of this series.)

I started gently up high with the hyoid, using the thumb and index finger, under the angle of the mandible. Staying lateral to midline, slide down to the broad, firm, thyroid lamina. At this point, use the index finger to come to midline and palpate the thyroid prominence in men. Lower down is the inferior cornu of the thyroid, bilaterally overlapping the cricoid cartilage. This is the bottom of the rhomboid, below which are the softer tracheal rings. Using the firm lamina of the thyroid as a guide (and especially if the thyroid prominence is not felt) the index finger is brought midline to the cricothyroid membrane at the inferior aspect of the lamina. In men, the thyroid cartilage is always more prominent than the cricoid, but in women they often have equal prominence.

After performing the laryngeal handshake with the dominant hand, switch to the non-dominant hand and grab the same landmarks. Use the non-dominant hand to stabilize the larynx (on the thyroid lamina) with the index finger over the cricothyroid. The dominant hand holds the scalpel and is stabilized on the sternum. Sternal stabilization is needed to make a controlled incision. We address this in part two of this series.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

6 Responses to “Tips and Tricks for Performing Cricothyrotomy”

February 10, 2015

Approaching the Awake Intubation - MarylandCCProject.org[…] “safely” in the risky zone. Welcome her to the resuscitation room with a gentle laryngeal handshake and be prepared to perform a surgical airway. Obviously, I have as much interest in performing […]

March 4, 2015

Approaching the Awake Intubation | Vinnie's ICU[…] think we’re “safely” in the risky zone. Welcome her to the resuscitation room with a gentle laryngeal handshake and be prepared to perform a surgical airway. Obviously, I have as much interest in performing […]

June 10, 2015

Approaching the Awake Intubation | University of Maryland[…] “safely” in the risky zone. Welcome her to the resuscitation room with a gentle laryngeal handshake and be prepared to perform a surgical airway. Obviously, I have as much interest in performing […]

August 25, 2015

Surgical airway training: technical and nontechnical skills and trainers | airwayNautics[…] that unanticipated difficult airways occur, always having a plan for failure and identifying the surgically inevitable airway early will help the team perform a surgical airway when it is required before too […]

September 10, 2015

Obesity Emergency Management | EM Cases : Emergency Medicine Cases[…] in obesity emergency management, Dr. Levitan recommends first identifying the midline using the laryngeal handshake technique or ‘rocking the rhomboid‘ and cutting a large vertical skin incision rather than first […]

May 4, 2018

emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine EducationEM Cases: Obesity Emergency Management - emDOCs.net - Emergency Medicine Education[…] in obesity emergency management, Dr. Levitan recommends first identifying the midline using the laryngeal handshake technique or ‘rocking the rhomboid‘ and cutting a large vertical skin incision rather than first […]